The Disruption to the Practice of Instructional Design During COVID-19

Introduction

This article details the experiences of practicing instructional designers (IDs) during the rapid shift from largely in-person to largely on-online experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Authors additionally spend time proposing implications for practice so that the lessons learned can be applied and further research can continue with this paper as a catalyst. The research methods, findings, and discussion are outlined below.

With the vast changes the pandemic has had on the role and practice of instructional designers, it is important to examine the perspectives of instructional designers working in the field. The article explores instructional designers’ perceptions of the impacts to and changes in the practice of instructional design in a time where practitioners found themselves rapidly moving content online in suddenly very visible roles in their organizations.

Guiding Research Question

Practicing instructional designers were asked to reflect on the following question related to their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic:

- How do instructional designers perceive the instructional design process has been disrupted by COVID-19?

Supporting Literature

The COVID-19 pandemic drastically altered the lives of individuals - disrupting personal relationships, work, education, the economy, how people spent their time, and both physical and mental health (Kessel et al., 2021). COVID-19 resulted in an unprecedented move to online learning, and in the shift to emergency remote teaching (ERT) within the public and private sectors, instructional designers, who were already situated at the intersection of teaching and learning online (Bessette, 2020), suddenly found themselves working quickly to figure out how to best support their stakeholders in a rapidly changing learning environment (Xie et al., 2021; Whittle et al., 2020). Prusko and Kilgore (2020) noted that during the pandemic, stories of “compassion fatigue” were common in the workplace, and this was no different for instructional designers, who had to help instructors move their courses online while listening to instructor frustrations, working long hours, and feeling overworked under the tremendous pressure of ensuring both academic and business continuity for their organizations.

While the role of instructional designers has not always been understood, the shift to online learning during the pandemic made the importance of instructional design very visible (Pilbeam, 2020; Prusko & Kilgore, 2020). Hodges et al. (2020) point out the important differences between ERT and carefully planned online learning; the former lacking in the careful planning usually given to online courses and programs which, when well designed, create learning experiences that are as effective as learning in a face-to-face environment. During the pandemic, instructional designers were building relationships in their communities, gathering and organizing resources, designing and delivering workshops to help their constituents learn how to teach with technology, providing support and advocating for their profession (Xie et al., 2021); however, they did not have the time to carefully design learning experiences in the same manner they normally would when given a regular course development cycle, which could take months (Hodges et al., 2020). Educators are starting to reflect on the impact of the COVID-19 crisis on education, and have recognized that more online teaching may become part of the new normal (García-Morales et al., 2021). With digital education expected to be a regular part of the instructional landscape, instructional designers, who were “acknowledged as a necessity” (Maloney & Kim, 2020, para. 5) during the pandemic, will continue to be in demand as digital learning partners within their organizations, in both higher education and corporations, to successfully create and support the delivery of online instruction as it becomes a regular part of how teaching and training is delivered.

Methodology

Participants

Graduate students at a large Research I University taking an Introduction to Instructional Systems Design course are asked to interview an instructional design practitioner as part of their final course project, thus participants in this study were selected by students, based on their contacts and networks, for the interview. The instructor then ensures that interviewees are currently practicing instructional designers. The 33 instructional designers interviewed, selected through a convenience sampling method, represented multiple job sectors, including higher education, healthcare, military and private industry. Interviewees consent to the interview with the understanding that a meta-analysis of themes from these interviews may be used for research purposes, and as part of the interview process, interviewees sign an interview consent form acknowledging that their responses may be used for research purposes.

Participants’ Work Context

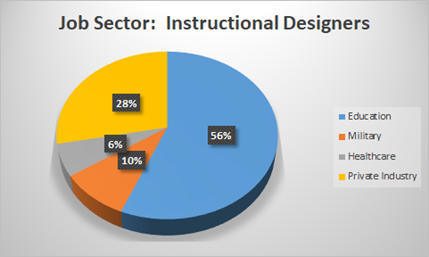

The 33 instructional designers interviewed represent multiple sectors of practice (see Figure 1 below). While the majority (56%) are practicing in educational settings (higher education public, private and community colleges), another 28% work in private industry in settings ranging from manufacturing to consulting firms, with representation from the healthcare industry and the military as well.

Figure 1

Job Sectors Represented by the Instructional Designers Interviewed

Data Collection Procedures

Students are given a standard set of questions (Appendix A) to ask during the interview, and as part of the interview process, students submit both a final paper and presentation comparing the theories learned in class to the practice of instructional design; students also submit their interview notes as an additional resource to supplement the interview. Several of the questions during the interviews conducted between March and June 2021 were directly related to the experience of instructional designers practicing during the COVID-19 pandemic, and responses were combined to answer the research question posed for this article. After vetting the interviews to ensure that all interviewees were unique, and that the interviewee addressed how the practice of instructional design was impacted by the pandemic experience, 33 interviews were deemed usable for the analysis.

Data Analysis

As this research is grounded in interview data, we applied a qualitative research approach (Creswell & Creswell, 2018) to analyze the interviewees’ experiences as instructional designers practicing in a pandemic, and used inductive reasoning from the interview components, which included a combination of student papers, interview notes and presentations. We specifically examined the interviewees’ responses to the pandemic related questions. Dividing into two teams, the authors reviewed the interview components relevant to pandemic related questions to ensure we had a shared understanding of the themes and observations emerging from the interview data and developed our codes collectively. An analysis template was created in Google Sheets, with participant types and data coded during a first pass of analyzing the data with each author primarily responsible for part of one semester’s dataset, and all authors responsible for double checking themes and codes that emerged from each semester’s data. While interviews can vary in how they unfold, interviewers asked specific questions to gather data in a purposeful manner, with themes for this paper emerging under the umbrella of specific questions related to the experiences of instructional designers during COVID-19.

Results

The research question addressed was: “How do instructional designers perceive the instructional design process has been disrupted by COVID-19?” In analyzing the responses, clear impacts were noted for the ID profession, challenges were documented that arose during the crisis, and opportunities were also observed.

Major Category 1: Pandemic Impacts

The interviews revealed a number of immediate impacts to the way training and instruction was designed, delivered and supported in an emergency remote instructional situation, the role of the ID, disruptions to social connections and the workload of instructional designers during the pandemic.

Impacts when Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) is equated with Online Instruction

The most obvious instructional impact during the pandemic was the rapid and unexpected shift in modalities from in-person to fully online instruction, both synchronously and asynchronously, across educational and business/training environments. One participant felt this shift would create a future expectation of increased online learning availability, “. . . this shift is now going to force the university into providing more online offerings, because this has now become the student expectation.” The same participant also cautioned, “. . . that there is a huge difference between providing . . . meaningful online learning experiences and offering online courses in response to a crisis or disaster.” There has been much discussion among instructional designers around the worry that instructors and learners forced into ERT during the pandemic might increase negative feelings about online teaching and learning (Hodges et al., 2020). Those who were resistant to online instruction may use their experiences during the pandemic as one participant in this study noted to “believe that is all online learning has to offer.” The same concern has been shared by designers around the students' experience of learning online during the pandemic. One participant shared, “In the same vein, students who experienced online courses during the COVID-19 pandemic may broadly attribute negative experiences to all online courses, when they know that just as with face-to-face courses, one course experience does not define all course experiences in that modality.”

Impacts on the Role of the ID

Instructional designers mentioned there was a large shift in their role during COVID-19. They had to approach their role differently under challenging time constraints, with a sudden and vast shift in the amount of ID work needing to be completed. As one interview participant observed: “Suddenly, IDs became very popular; their uniquely positioned skillset that comprises the knowledge of technology to support distance learning and the knowledge of effective pedagogy for successful learning outcomes.” Another participant noted that the pandemic meant that IDs that may have not worked together before began collaborating “to assist with the increase in requests and centralize support, and various groups have come together as a support network.” Further, IDs had to let go of old models and embrace more agile models, with participants mentioning in their interviews how they had to rapidly pull online instruction together, not always systematically following their preferred ID model. IDs also had to prioritize differently which projects would get done; as one participant noted: “This sudden change in learning environments caused some things to have to get prioritized over others, and some items had to be placed on the back burner.”

Social Connection Impacts

Some negative impacts to social connections were mentioned around the lack of being able to read body language and interpret tone of voice, both in designing and delivering instruction. One participant offered “that less in-person contact keeps learners and facilitators from building social connections with one another and that online instruction does not allow facilitators and learners to read one another's body language and tone of voice.” One participant who was new on the job had never met his team in person, stating he missed the casual conversations that happen in the hallways or at the “watercooler” that would have helped him feel more a part of the work culture. In contrast, some positive impacts to social connections were also reported around increased access to stakeholders; as mentioned by a participant, “the pandemic has increased the acceptance of virtual meetings, often held on a video conference platform such as Zoom. While technology like this has made it easier to connect with stakeholders, it may also be a crutch for the future of collaboration.” Positive impacts to internal social connections were depicted by a participant as “their team and faculty adapted to virtual development meetings, gave each other grace, and accomplished goals as intended. Notable changes included rapport was built more quickly, as both faculty and IDs took time to check in on each other’s mental and physical health during meetings and discussions touched on family members or what was observed from each other’s backgrounds or home surroundings.”

Workload Impacts

As with social connections, workload was discussed by participants in both a positive and negative light. Some participants mentioned using the time they would have taken traveling back and forth to work each day as extra time they could dedicate to getting work done. With travel halted, they “actually had more time to focus on instructional design work.” Some negative impacts mentioned were around increased workload such as helping with increased training needs. One designer working in a higher education context emphasized:

that more time is needed to acclimate faculty who are new to some of the software and hardware programs that they need to use to meet and work seamlessly. They must accommodate varying schedules and occasionally had to elongate development times due to instructors’ competing priorities. They were always exploring ways to modify, improve, and update their processes to ensure they can meet the needs of students and instructors. Rapid design and agile models have been considered in the past and they are currently being explored. As noted previously, the challenge is the time commitment.

Participants reported that clients expected training to be designed and delivered online very quickly. One participant mentioned, “we have received a lot more requests for eLearning. We have also done a good deal of rapid design to get the volume of information needed by our learners out to them quickly.”

Major Category 2: Pandemic Challenges

The interviews revealed a number of challenges faced by instructional designers that flowed from the impacts of instructional delivery changes under extreme time pressures and increasing workloads. Instructional designers found themselves overwhelmed with support requests with a lack of time to design instruction carefully, challenges for both themselves and their learners in accessing technology, resource and staffing challenges, and the challenges of both IDs and SMEs and instructors and students only being able to meet from a distance.

Time Challenges

Clearly, the instructional design professionals in this study saw challenges around time to be some of the most impactful, with one participant noting that “my time would be the thing most disrupted by the pandemic, meeting the needs quickly to get online." Time (or lack thereof) played a role in their ID work in a variety of ways, including taking shortcuts on applying all aspects of ID models such as ADDIE. The incredibly quick shift to online learning was overwhelming at first. One instructional designer explained how they were working furiously to transition their own courses in the graduate school to online modules while helping others to do the same, and struggling to find the time to do so. Others noted that they were caught in a crunch as the needs for online learning development increased when at the same time the urgency for getting them completed increased. As one ID noted, “clients wanted much more training on a more rapid timeline.” One instructional designer in higher education emphasized that more time was needed to acclimate faculty who were new to the software and hardware needed to do their work, stating: “We had to accommodate varying schedules and occasionally had to elongate development times due to instructors’ competing priorities.” In many cases, IDs also had to update their own skills. The need to find ways to modify, improve, and update their processes to rapidly meet the needs of students and instructors was a constant issue, and rapid design and agile models gained more attention from designers as they struggled to manage their time with all of the demands placed upon them (Czeropski & Pembrook, 2017).

Access and Communication Challenges

Instructional designers, especially those involved in education, often had frustrating issues with access and therefore, were concerned not only with their ability to work with SMEs, but with instructional equity for their learners. One participant noted that his biggest challenge was around the inequity of internet availability and consistency, stating that “some students live in rural areas that do not have access to sufficient internet speed to be able to use online instruction.” This meant that students not only had issues accessing course material, but also challenges in accessing their instructors. Access issues such as these lead to issues of equity as often the students affected are already maneuvering disadvantages and the pandemic acted to magnify these. Through no fault of their own, some students had bigger hurdles to leap in order to succeed (Nguyen et al., 2020). Instructional designers outside of educational institutions also experienced challenges with access and communication. Participants noted that the social distancing and group gathering rules made it difficult not only for the learner, but for the design process, as access to the SMEs needed to create course content was impacted. As mentioned by one interview participant who was reflecting on the challenge of working with others to design courses: “Due to COVID, the ability to build these strong, personal connections has become difficult. This has in turn caused overall communication and getting people on board with certain project ideas more difficult.”

Resource Challenges

During the pandemic, access to adequate resources came up as a challenge with instructional designers. Some institutions and businesses were ready when the crisis hit and had all of the technological tools needed in place for employees to do their jobs even with the pandemic shifting instruction online. Others had to acquire tools (software and hardware) and sometimes knowledge (requiring financial resources for training) to do their work at a distance, often competing with other needs. Some participants noted they were able to get additional resources if articulating the need to their company; one interviewee stating “they can find that budget if you can explain well and they sense the importance.” Even when getting money for needed resources, nationwide computing shortages (Caine, 2021) added to the problems as even obtaining needed resources to work remotely became challenging with supply chain issues.

Staffing Challenges

The needs brought on by the pandemic were so swift that there was not enough time to get people in place to do the work. IDs noted that they often had to collaborate with other units to complete work and build an adequate support network. While some employers were able to hire to meet increased demands on IDs, others suffered staffing reductions. The pandemic hit some businesses hard and the work stoppages in one sector affected others. Sectors such as restaurant and travel were some of the hardest hit, with one participant stating “a major impact of the pandemic on the office has been the reduction in staff, from a team of seven down to a team of four. There is no timeline for when the office can expect to be fully staffed again in the future.” Staff changes also translated to issues with onboarding. As a new employee, one designer was “thrown into a strong culture while never meeting his team members in person,” noting that joining a new team “was a difficult task socially, however professionally, they were able to complete tasks and continue to communicate effectively.” Virtual onboarding needs have caused businesses to alter their onboarding processes (Prince, 2021).

Challenges of Working and Learning at a Distance

Businesses that continued work during the pandemic saw massive increases in training needs (Lohr, 2020). As one participant put it “events like a deadly virus actually prove there are even greater needs for training as the new way of work, like working from home without the supervision of leaders, reveals cracks in the foundation, aka, training needs.” But the challenges associated with needing to be apart from one another were apparent. A designer for the military noted that it was difficult to complete large-scale operations due to restrictions of both group size and proximity. Another noted the difficulties this situation created when working with SMEs, with one participant observing “it is the job of the ID to guide the instructional project based on the identified learning outcomes, in cooperation with an SME. If all three participants are unable to meet in person, there may be a disconnect between the goals of the client and the understanding of the ID and SME.” Distance affected learning, too, as there were impacts on the social connections of learners, as discussed earlier.

Implications for Practice

The findings of this study suggested that COVID-19 significantly impacted the current work of instructional designers. During the pandemic, interviews with IDs revealed a number of immediate impacts to the way training and instruction was designed, delivered and supported while recognizing the increasingly visible role of the instructional designer. Challenges such as increasing workloads, the need to leverage more technology and the need to design at scale for flexible and online instruction were recognized during the pandemic. The pandemic also presented IDs with opportunities that can positively shape the future of this increasingly visible profession; opportunities to collaborate with stakeholders to design truly engaging instruction in a variety of settings, from higher education to corporate environments.

Implications for Practice 1: Considering the Flexibility of Instructional Design Models

All of the practitioners interviewed for this study followed an instructional design model, with ADDIE, or some version of it, being the most commonly used. Several of the instructional designers interviewed mentioned being more agile and flexible in their applications of ID models during the pandemic, and while they expect to continue to follow ID models in the future, several interviewees noted the need to be more flexible when applying ID models to practice. In additional to a strong foundation in learning theory and instructional design models, instructional designers also need excellent communication and other soft skills (diplomacy, persuasion, emotional intelligence) to work with a variety of other subject matter experts (SMEs) (Ritzhaupt & Kumar, 2015), and several practitioners mentioned the necessity of applying any ID model within a framework of collaboration and empathy.

Implications for Practice 2: The Increasing Visibility of the Instructional Design Profession

That the visibility of the practice of instructional design has forever changed was a consistent theme from the interviewees. What may have felt, as one of the interviewees described, as “invisible labor that happens behind closed doors,” is now strikingly visible. Perhaps the work of IDs had indeed not been well-understood (Pilbeam, 2020; Prusko & Kilgore, 2020); however, the shift to online instruction during the pandemic, with the often poorly designed remote emergency teaching and training those individuals experienced, has clearly raised the visibility of the need for a solid ID process to design hybrid and online instruction.

Implications for Practice 3: Clearly Differentiating Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) from Online Instruction

The online design and instructional experience quickly gained by instructors during the pandemic is quite different from following an intentional design process where the work has been planned well in advance with carefully crafted activities, measurements and the learning experience in mind. Because of the negative experiences that many had especially early on in the pandemic as recipients of educational or training experiences delivered with last minute planning, there remains a need for practitioners to clearly articulate for all stakeholders the difference between ERT, and courses and experiences designed with an appropriate amount of time. With that said, there have been some very valuable lessons learned for those designing and instructing during ERT times, and it is important to ensure those lessons learned do not fade away. Instructional designers worked hard during the pandemic to make remote work feasible, creating efficiencies when meeting with SMEs and often adding in more checkpoints within the ID process. They learned to flex ID models when needed and to be more iterative in order to respond to the scale of the need. While high-quality online instruction takes time and resources to support the design, delivery, and evaluation of courses, and requires revision for continual improvement, IDs made it work during the pandemic.

Recommendations for Future Research

Instructional design practice during the pandemic created some unique challenges and opportunities that lead to practices and approaches that require long-term consideration.

Instructional Design Models

While ADDIE was the model most often relied on by the instructional designers interviewed, the practice of applying ID models during the COVID-19 pandemic was impacted significantly by the pressures of time, and while many IDs kept their ID frameworks as a touchstone, the interviews suggested that more agile approaches were being used in actual pandemic practice. Practitioners were embracing newer ID models out of necessity, and a question for ID practitioners remains: when the dust settles from the pandemic, what will be the ID model followed? The pandemic experience necessitated the application of agile practices, the embrace of newer ID models and/or a very non-linear application of existing models. Future research needs to consider what instructional design models fit the new era of instructional design and ask; is it time to retire, re-embrace or revise ADDIE? And as many ID practitioners experienced when dealing with exhausted stakeholders during the stress of the pandemic, should future ID models be grounded within the context of empathy?

Create Standardized Intake Forms for ID Assistance for Instructors

Instructional designers during the pandemic had to assist an extraordinary amount of people in an incredibly short amount of time with limited resources. Some interviewees mentioned creating checklists or handing out guides for SMEs they worked with to help move along the intake process for creating instruction. Future research could look more closely into how practitioners could create guided help for non-ID practitioners; creating forms or templates that guide others to give their ID input in a way that makes the IDs work more efficiently. If IDs had questions in advance for people to respond to within their contexts that could help them get ahead in the actual instructional design process, it might assist IDs in managing a heavier workload. During COVID-19, instructional designers were asked to do “all the things;” maybe future expectations of SMEs would help them do more of the front end of the ID process, a process that many SMEs came to appreciate more during the pandemic.

Resilience Ready IDs

Some interviewees noted that “it didn’t affect me” or their organizations when the pandemic hit, indicating that they did not feel the impact within their training and teaching space. Why was that the case? An interesting research question would be to dig deeper into why some interviewees and/or organizations did not seem as impacted. Is it because they were already fully online? Were they simply already technology savvy with a solid fluency in the practice of instructional design to the extent that big changes did not impact them? Were they already well resourced? Were the practitioners simply very resilient individuals? Did they have detailed academic or business continuity plans? Understanding who was more “ready” for a disaster such as the pandemic and why might help inform training for practitioners and groundwork for organizations that could ensure they are ready for any future tectonic plate shift in how learning is done by and for their organization.

Expanding the Conversation

While a few of the interviewees practice within multi-national companies, the majority of interviewees were physically located in the southeast region of the United States. Additionally, none of the interviewees for this study are practitioners in the K-12 instructional/curriculum design space. Future research could include a more geographically diverse sampling of instructional design practitioners, include K-12 practitioners, and consider any additional unique needs and challenges that arose for instructional designers who were creating materials for multi-lingual learners during the pandemic.

Conclusion

While what instructional designers do each day may not have been understood pre-pandemic, those interviewed for this study agreed that the rapid shift to online teaching and training during the pandemic made the importance of good instructional design very visible (Pilbeam, 2020; Prusko & Kilgore, 2020). Moving forward, interviewees believed that more job opportunities will exist for instructional designers across many different organizations as the value of well-designed education and training became increasingly understood during the pandemic. Clearly, the rapid shift to online learning made the importance of carefully designed instruction visible and the role of the instructional designer valued.

The future of instructional design is evolving. Traditional ID models will continue to flex as instructional designers are asked to work on multiple current projects across a myriad of learning environments (face-to-face, hybrid, hyflex and online). Both educational and business environments will increasingly leverage the role of the instructional designer in creating meaningful learning environments that are very different from the emergency remote teaching environments that learners experienced early on during the pandemic. Pandemic lessons learned will be applied, and the future is promising for instructional designers as a key partner in organizational success.

References

Bessette, L. S. (2020). Digital learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Teaching and Learning Forum, 29(4), 7–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/ntlf.30241

Caine, P. (2021, July). Global shortage of computer chips hits US manufacturing. WTTW News. https://news.wttw.com/2021/07/29/global-shortage-computer-chips-hits-us-manufacturing

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications, Inc.

Czeropski, S., & Pembrook, C. (2017). E‐Learning ain't performance: Reviving HPT in an era of agile and lean. Performance Improvement, 56(8), 37-45. https://doi.org/10.1002/pfi.21728

García-Morales, V., Garrido-Moreno, A., & Martín-Rojas, R. (2021). The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1-6. https://doi.org/https:/dx.doi.org/10.3389%2Ffpsyg.2021.616059

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T. & Bond, A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Kessel, P. van, Baronavski, C., Scheller, A., & Smith, A. (2021). How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed Americans' personal lives. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/2021/03/05/in-their-own-words-americans-describe-the-struggles-and-silver-linings-of-the-covid-19-pandemic/.

Lohr, S. (2020, July 13). The Pandemic has accelerated demands for a more skilled workforce, New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/13/business/coronavirus-retraining-workers.html

Maloney, E., & Kim, J. (2020). Learning and COVID-19. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/blogs/learning-innovation/learning-and-covid-19

Nguyen, M. H., Gruber, J., Jaelle, F., Marler, W., Hunsaker, A., & Eszter, H. (2020). Changes in digital communication during the COVID-19 global pandemic: Implications for digital inequality and future research. Social Media + Society, 6(3), 1-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2056305120948255

Pilbeam, R. (2020). The COVID-19 wake-up call: Instructional designers are key to creating accessible and inclusive learning models. The EvoLLLution. https://evolllution.com/programming/program_planning/the-covid-19-wake-up-call-instructional-designers-are-key-to-creating-accessible-and-inclusive-learning-models/

Prince, N. R. (2021). Transitioning to a 100% virtual onboarding process during the COVD-19 pandemic: An interview with Kat Judd, Vice President of people and culture at Lucid, Business Horizons, 65(4), 413-416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2021.03.004

Prusko, P., & Kilgore, W. (2020). Burned out: Stories of compassion fatigue. EDUCAUSE. https://er.educause.edu/blogs/2020/12/burned-out-stories-of-compassion-fatigue

Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Kumar, S. (2015). Knowledge and skills needed by instructional designers in Higher Education. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 28(3), 51–69. https://doi.org/10.1002/piq.21196

Xie, J., A. G. & Rice, M.F. (2021) Instructional designers’ roles in emergency remote teaching during COVID-19, Distance Education, 42(1), 70-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869526

Whittle, C., Tiwari, S., Yan, S. & Williams, J. (2020), Emergency remote teaching environment: a conceptual framework for responsive online teaching in crises, Information and Learning Sciences, 121(5/6), 311-319. https://doi-org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/10.1108/ILS-04-2020-0099

North Carolina State University

This content is provided to you freely by EdTech Books.

Access it online or download it at https://edtechbooks.org/jaid_11_2/the_disruption_to_th.