For the Common Good

Recommitting to Public Education in a Time of Crisis

Introduction: Center for the Improvement of Teacher Education and Schooling: An Explanation and An Invitation

Steven Baugh, Former Director, Center for the Improvement of Teacher Education and Schooling (CITES)

The relationship between democracy, schooling, and educational renewal should not be taken lightly. They are interconnected in ways that, taken together, form a magnificent tapestry of human freedoms and dignity.” -John Goodlad

For 37 years the Brigham Young University-Public School Partnership has been guided by a philosophy built on the relationship among democracy, schooling, and the concept of educational renewal.

Our democratic way of life cannot be taken for granted or assumed to perpetuate itself without any effort on our part. Critical to its existence is public education. We as the American public need to understand and define the role that our public schools play in promoting and sustaining our form of democracy. Democracy in this report is recognized as a form of civic life and a political system with underlying ideals, values, principles, and institutions. Our reference will be to the American form of democracy, more precisely identified as a democratic republic.

The message of this review contains both an explanation and an invitation. The explanation comes in three sections and addresses in each a fundamental question:

How are democracy, public virtue, and education of our youth related?

Should the preparation of our young for democratic citizenry be the primary purpose of our schools?

What is the Brigham Young University- Public School Partnership doing to develop democratic citizens?

We extend to all the invitation to enter into conversation with us about the relationship between public schools and democracy. Questions have been inserted to guide thoughtful discussions that you might hold with colleagues, friends, and concerned citizens. The Agenda for Education in a Democracy remains at the core of our efforts in this 37-year-old university-public school partnership.

How are democracy, public virtue, and education of our youth related?

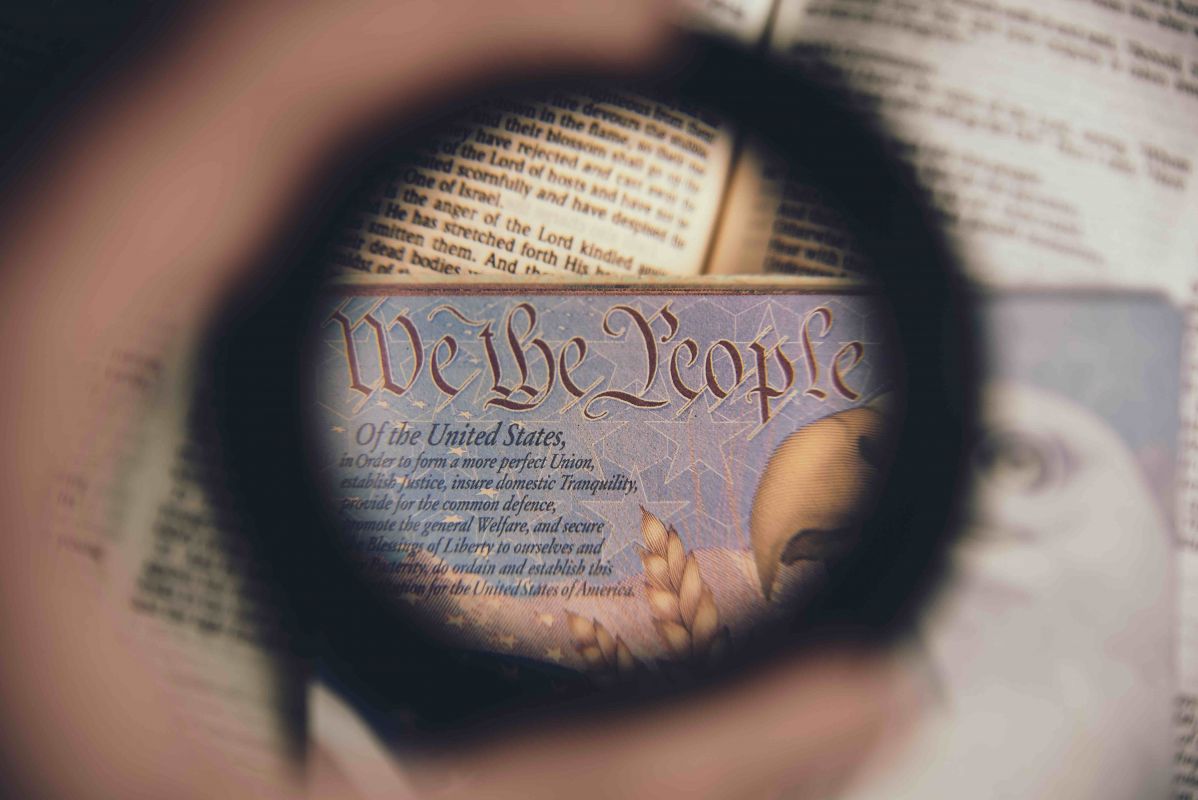

Photo by Anthony Garand on Unsplash

We the people . . .

Democracy involves making decisions. Every day we make decisions as individuals on issues such as where we live, what job we hold, how we spend our time and money. In making these types of decisions we become personally responsible for the choices we make. When we participate in making decisions with other people, we must find a way to share in the process and responsibility for these collective choices. The underlying principle of democracy is that all members have the right to take part equally in the decisions that affect them. The people are considered the foundation of political life and are best suited to determine the interests and goals of the society

. . . government of the people, by the people, for the people . . .

Discussion Question: Are people able to reach a view of what is best both for themselves and for the nation as a whole?

For the common good . . .

In a democracy individuals govern themselves. Individuals are at liberty to make fundamental choices and the will of the people as a whole is recognized through majority rule and respect for the minority. A major challenge for a democratic system is how to structure the relationship between the individual and the community. That is, how do you honor the multiple interests of individuals and the needs and well-being of the large group or community? Inherent in a democratic government is this tension between individuality and common good. The type of government established reflects the aspirations of it citizens in their desire to live together. It represents the balance achieved between individual rights and the common good.

Discussion Question: Are all citizens capable of making decisions on how to govern our public life together?

Moral responsibilities of governance …

Democracy requires all citizens to share in the moral responsibilities of governance, both with respect to their own individual behaviors and to the extent necessary to ensure the well-being of others and the common good.

Discussion Question: How does having a democratic form of governance influence public virtue?

Public virtue . . .

From its founding citizens of our nation have recognized the need for “public virtue” in securing the freedoms and liberty offered in a democratic republic. Gordon Wood summarized this need when writing:

In a monarchy, each man’s desire to do what is right in his own eyes could be restrained by fear or force. In a Republic, however, each man must somehow be persuaded to submerge his personal wants into the greater good of the whole. This willingness of the individual to sacrifice his private interests for the good of the community—such patriotism or love of country—the eighteenth century termed public virtue. A republic was such a delicate polity precisely because it demanded such an extraordinary moral character in the people. Each state in which the people participated needed a degree of virtue; but a republic which rested solely on the people absolutely required it, although a particular structural arrangement of the government might temper the necessity for public virtue, ultimately no model of government whatever can equal the importance of this principle, nor afford proper safety and security without it (Gordon S. Wood, The Creation of the American Republic, 1776-1787 (New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1969).

The historian Richard Bushman wrote about the importance of virtue in the minds of those who framed our founding documents.

Many of the early leaders of this country were persuaded that free government could not survive unless the people were virtuous. By virtue they meant essentially two things: first, the avoidance of luxury and self-indulgence, and secondly, the sacrifice of personal interest for the good of the whole. They used patriotism as a synonym for virtue, but their definition of patriotism was different from the current definition. It did not mean loyalty to one’s country in contrast to other countries of the world, but loyalty to the country as contrasted to the self. The patriot was one who served the public good rather than the private good. Kennedy’s electric statement, “Ask not what your country can do for you, but what you can do for your country,” was fully in the spirit of the eighteenth-century definition of patriotism or virtue (Richard L. Bushman, Virtue and the Constitution, printed in “By The Hands of Wise Men”: Essays on the U.S. Constitution, Ray C. Hillam, Editor, 1979, Brigham Young University Press, Provo, Utah).

Core moral values ….

When the Constitution of the United States of America was written it contained a preamble. The purpose of this preamble was to explain the reasons and general purposes for this newly proposed form of government. “We the People” informed all that the listed purposes were the aims and desires of the citizens of the nation. Each and every citizen had some responsibility to “form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.”

Discussion Question: How are citizens prepared to participate in a democratic form of government?

Should the preparation of our young for democratic citizenry be the primary purpose of our schools?

Photo by Vasily Koloda on Unsplash

A more perfect union . . .

Lane and Oreskes (The Genius of America) view this articulation as an act in which “the framers created a new definition of public virtue.” They continued,

Before, public virtue had meant setting aside a self-interest to accept a general public interest. Now it assumed that Americans would pursue their self- interest within the halls of government. But if their voices were meaningfully heard, they would respect for the greater good decisions even when adverse to their views. Participation, compromise and respect for process would become the new measure of public good.

In order for citizens to create and form a more perfect union, it would be necessary to participate in ways that would bring about the political action required to meet the purposes of the government and preserve an individual citizens’ quality of life. In other words, it is not only the democratic ends that are important but also the means for achieving those ends must be democratic in nature.

Social and political democracy …

Making political democracy work is challenging, but maybe even more challenging is social democracy: the living together of people endeavoring to follow democratic ideals. A commitment to democracy affects all aspects of life. We sometimes make the distinction between a social and political democracy. Democracy may be seen as a form of civic life and a political system with parties, officials, and institutions. Civic life refers to the public life of citizens that is concerned with common affairs and mutual interests of the nation. Democracies promote the common good, that is, it acts on behalf of the common welfare. Democracy as a form of government requires a social fabric that is democratic. Because people are not born with the traits necessary to sustain a democratic way of life, they must be acquired through education.

Discussion Question: Where and how are the skills and dispositions of democratic citizens learned?

Becoming a public . . .

Benjamin Barber wrote, “Public schools are not merely schools for the public, but schools of publicness: institutions where we learn what it means to be a public and start down the road toward common national and civic identity” (Public Schooling: Education for Democracy, p. 22).

Discussion Question: Are public schools the ideal place to create democratic citizens?

One educational leader who strongly advocates that the primary purpose of public schools is the development of democratic citizens is John Goodlad. The reason why schools are ideal for this purpose is that they are indeed public places, where different groups of people are brought together on a frequent basis in which discussion and decisions can be made about common problems. Other claims by Goodlad include:

- As a nation we have a moral responsibility to prepare our young for participation in the complex system of social and political organization that we call

- Education provides for all citizens the necessary apprenticeship in the understanding and practice of

- No political and social system as ambitious, complex, and idealistic as a democracy can ever hope to survive—let alone thrive— without citizens to sustain Schools play an essential role in creating and sustaining such citizens.

- Skills, dispositions, and habits of intellect necessary for democratic citizenship have to be developed somewhere as people are not born with The school is the only institution in our nation specifically charged with enculturating the young in a social and political democracy.

- Democracy’s tomorrow depends very much on what goes on in classrooms

- America’s public schools are the moral responsibility of the public at

The Agenda for Education in a Democracy (AED) & the BYU-Public School Partnership

The AED is essentially a vision of education which identifies the primary public purpose of schooling to be that of developing democratic citizens. The Agenda provides a plan of action which brings together the coordinated efforts of the members of the Brigham Young University-Public School Partnership. The AED has guided the thinking and action of the Partnership for the majority of its 37-year existence. The Partnership has served as a “proofing” site for many of the ideas and beliefs put forward regarding democracy and the schools. The vision of the Agenda also articulates the moral grounding of how schools should be conducted and how teachers should be prepared.

The Brigham Young University-Public School Partnership (BYU-PSP)

In April of 1984 the BYU-PSP was formally organized. Over the years a number of seemingly simple claims regarding the improvement of schooling and the preparation of teachers have been made and experimented upon. Chief among these claims has been the recognition of the fundamentally moral quality of both education and schooling. Schooling is a moral undertaking because what transpires there can have a significant impact on a child.

The importance of public education has been reinforced by the belief that public education is needed in order to prepare all of its members for democratic citizenry. A recognition has developed that public schools are perhaps the only public institution available for rigorously promoting and sustaining our social and political democracy, but that schools cannot in and of themselves make anyone wise. Schools can provide a foundation and some basic building blocks that will help people become wise citizens.

The AED had been derived from four basic purposes of schooling, often referred to as the “moral dimensions of teaching.” Each of these purposes or missions has moral considerations underlying its activity. These include:

- Enculturating the young in a democracy

- Providing access to knowledge for all children and youth

- Practicing a nurturing pedagogy

- Serving as stewards of schools

The Three Cs: Character, Conduct, Citizenship: The David O. McKay School of Education Perspective

“It is well for educators everywhere when teaching the young to have in their mind the three Cs as well as the three Rs mentioned so proverbially. By those three Cs I mean character, conduct, and citizenship.” -David O. McKay

Then to leave no doubt of the importance of these aims in our public schools he said, “The teaching of religion in public schools is prohibited, but the teaching of character and citizenship is required.” All educator preparation programs at Brigham Young University have adopted as part of its conceptual framework the four moral dimensions of teaching. These dimensions are informed by the beliefs and principles expressed in President McKay’s 3 Cs.

What is the Brigham Young University- Public School Partnership doing to develop democratic citizens?

Photo by Cytonn Photography on Unsplash

BYU-Positive Behavior Support Initiatives

Eight-year-old Brian stands alone on the edge of the playground. Gathering courage, he walks to- ward another student. “Hey Mike, how’s it going?” He pushes the button on the counter hidden in his pocket and glances at Ben, a popular boy who is standing a few feet away; Ben grins and operates his own counter to record Brian’s social interactions. Brian is struggling with social anxiety and deficient social skills; Ben is his peer helper.

Ms. Brown, a middle school teacher begins her “writing assignment.” Three students in her English class are displaying emotional/behavioral problems and have been identified as at-risk via school-wide screening. For two boys with aggressive disruptive behavior, she notices positive behaviors worthy of a praise note. She reaches for the journal of Susan, who suffers from depression, reads the girl’s latest entry, and responds in writing with compassionate encouragement.

Both of these scenarios illustrate participation in a nurturing pedagogy in which civility is fostered. Ben and Ms. Brown are learning to balance their own desires for sociability or personal time with the public good: helping disruptive students learn to control themselves and reaching out to withdrawn students. The at-risk students learn that lashing out and with- drawing are not the best ways to handle problems, and they gain some idea of their own importance as citizens within their school communities.

These examples are typical of the work of the Positive Behavior Support Initiative (PBSI), designed by McKay School faculty/administrators and implemented through CITES. PBSI partners with schools to develop empirically-based systems that support nurturing pedagogies, the development of civility and social competence, and effective practices for at-risk students.

Beverly Taylor Sorenson BYU A.R.T.S. Partnership: Arts Reaching & Teaching in Schools

In a school auditorium, first grade students are creating a dance based on a painting by their principal. They decide what each child will represent, then work out ways to bring individual sequences of movement together to form “group shapes” within their choreography.

In a second grade classroom students are clustered around a very long stretch of paper, working on a mural titled “Our Neighborhood.” All contribute ideas, and each draws his or her portion.

In a fifth grade classroom students are randomly assigned roles representing different races, ages, and occupations and are seated on a segregated “bus” from the Rosa Parks era. Students perform their roles, then express how someone in their role would be feeling.

All of these scenarios show children learning how to engage in democratic living: balancing their individual ideas and contributions with the goals and needs of group creation. The A.R.T.S. Partnership is bringing democratic experiences into the schools through visual arts, media arts, music, dance, and drama. Arts are both taught/experienced independently as arts, as in first grade scenario, and integrated into other curricular areas such as literacy or social studies, as in the second and fifth grade scenario. Programs of the A.R.T.S. Partnership include workshops and mentoring to build teacher capacity to provide all children opportunities to engage in the arts.

Associates Program

When we say students need to experience democracy in a classroom, do we mean that they vote on assignments, due dates, and behavior expectations?

The high school history teacher and the university social studies methods teacher affirm, “It’s certainly worked well for us!”

The band director and the football coach respond vigorously, “That would be a disaster. The majority can’t rule on whether to pass a football or how to play a piece of music.”

The ESL teachers wonder if it’s hypocritical to teach democracy: “Our students’ parents can’t vote, and the kids are treated as a underclass at school.”

This group of educators, participants in an associates cohort, are experiencing democracy as well as talking about it. Their experiences, perspectives and viewpoints are as different as their roles in their school district. Each defines and applies democracy differently. In this small group each is able to voice a position and feelings, and each is exposed to viewpoints not considered before. Each expresses: each learns. Each places individual needs and views in context with those of others, weighing them in terms of common good. Later small group ideas will be publicly shared.

Each district conducts its own cohort that are composed of public-school personnel, along with both school of education and cross-curricular faculty from BYU. They meet for five two-day retreats over a year’s time to explore the moral dimensions, with a variety of discussion formats and activities. They all read a selection of books and articles as preparation. A cohort may never totally agree on a definition of democracy or a list of appropriate classroom applications, but they learn to respect and relate to a diversity of individuals and ideas.