HyFlex for Tutors

Professional Development for HyFlex

Jerrylynn Manuel and Katrina Watt are instructional designers (IDs) within the eLearning team at the Southern Institute of Technology (SIT)/Te Pūkenga. This is their account of the support system employed to upskill teaching staff for HyFlex delivery at SIT’s main campus in Invercargill (the largest city in New Zealand’s Southland region).

SIT’s HyFlex beginnings

SIT is the sixth largest polytechnic in New Zealand with more than 12,000 students enrolled in at least 200 programmes (Southern Institute of Technology, 2024). In 2023, it officially became a subsidiary of the larger vocational education network known as Te Pūkenga. At present (January 2025), SIT consists of five campuses distributed across the South Island and offers a wide range of delivery options (i.e., face-to-face, blended, HyFlex, and distance) (Figure 1). Of them, hybrid-flexible (HyFlex) is the most recent addition.

Figure 1. Locations of SIT Campuses Across the South Island of New Zealand

Several events led to the implementation of HyFlex delivery at SIT. Prior to the organisation’s adoption of it, SIT experimented with blended delivery with two schools (Therapeutic and Sports Massage; and Sport, Exercise & Recreation) trialing it. In July 2021, a blended-delivery pilot course in the Screen Arts programme changed its delivery mode when it permitted simultaneous in-person and online participation, upon the request of those enrolled (Koller et al., 2023; Manuel, 2022). Approximately one month later, New Zealand went into lock-down for the second time due to the spread of the COVID-19 Delta variant. The pilot was one of the few on-campus courses that easily transitioned to online teaching during the three-week period. After successfully gaining senior management buy-in through various means (i.e., an initial proposal drafted by Jerrylynn, a business case developed by eLearning’s team lead (Emma Page), and two presentations for senior managers on the pilot’s success and how HyFlex may be used to connect delivery across all of SIT’s campuses), it was decided in December 2021 that HyFlex delivery be rolled out across the institution starting with Year 1 Bachelor of Screen Arts courses and the ITC602 Special Topics (Cloud Computing) course. Due to its expansion, a means of supporting teaching staff was deemed necessary. As of the end of 2024, there are at least 65 courses offered in HyFlex and approximately 25 instructors who are teaching in that manner.

The rationale behind the support system’s design

Engaging teaching staff as IDs (i.e., designers of learning experiences) was identified as the most pragmatic way of onboarding those new to HyFlex teaching. Based on the support provided to the instructor responsible for the pilot course (Rachel Mann) and early discussions with the Bachelor of Screen Arts teaching team with regards to blended delivery, it was evident that assisting them with content creation was not appropriate or required. Several other challenges justified this approach as HyFlex rolled out further across the institution such as the high HyFlex instructor to ID ratio, and the short period between design and delivery. Furthermore, because all IDs (Jerrylynn, Katrina, and Balint Koller (former SIT ID)) hold various qualifications in education and possess a broad range of experiences in the field, it was natural for them to gravitate towards a teaching model of support. As such, professional development on HyFlex course design and facilitation was chosen as the best means to upskill teaching staff.

IDs drew upon various sources to create HyFlex for Tutors, the support system devised. For instance, the instructional coaching element was modelled after that of the Universal College of Learning’s Te Atakura (Universal College of Learning, n.d.) support system that Jerrylynn was a part of in the capacity of coachee. Information on course design provided to instructors was originally underpinned by the principles of HyFlex (Beatty, 2007) and those of Networked Learning (Networked Learning Editorial Collective, 2021). Now, the Community of Inquiry (COI) framework (Garrison et al., 2000) and Universal Design for Learning (UDL) (Center for Applied Special Technology, 2024) have been included in the mix. In the support system’s latter iteration, Katrina’s primary and secondary sector teaching experiences helped to inform the evaluation method used to determine instructors’ readiness to be independent HyFlex practitioners. Moreover, based on IDs’ and early adopters’ (i.e., the Screen Arts teaching team) teaching philosophies, the system was designed to be collaborative with the former working alongside instructors during all phases of their journey (i.e., prior to, during, and after delivery) over a three-semester period. The hope was that this would increase the likelihood of facilitating changes to teaching practices and perceived levels of preparedness, and engage instructors in designing from the student point-of-view at the first instance. On a wider level, its design and implementation were a conscious effort to alter the organisation’s current siloed means of working. And so, the support system devised was and continues to be grounded in personal, contextual, and theoretical perspectives.

The support system’s constituent parts

The first iteration of the support system has been documented elsewhere (Manuel, 2022). In its most current form, instructors have access to a self-paced course on HyFlex teaching, a Community of Practice (CoP), an ID-led coaching service, and IT-supported technology services. In terms of the first element, the HyFlex for Tutors Blackboard course is where resources related to the following are located: HyFlex principles, strategies on building greater teaching presence and engaging learners in an online space, and teaching exemplars from within the organisation (Figure 2).

Figure 2. HyFlex for Tutors Blackboard Course

Once enrolled in the Blackboard course, new HyFlex instructors are also granted access to the communication hub (i.e., HyFlex for Tutors Microsoft Teams Classroom), which is used to facilitate the CoP’s 30-minute monthly meetings (Figure 3).

Figure 3. HyFlex for Tutors Microsoft Teams Classroom

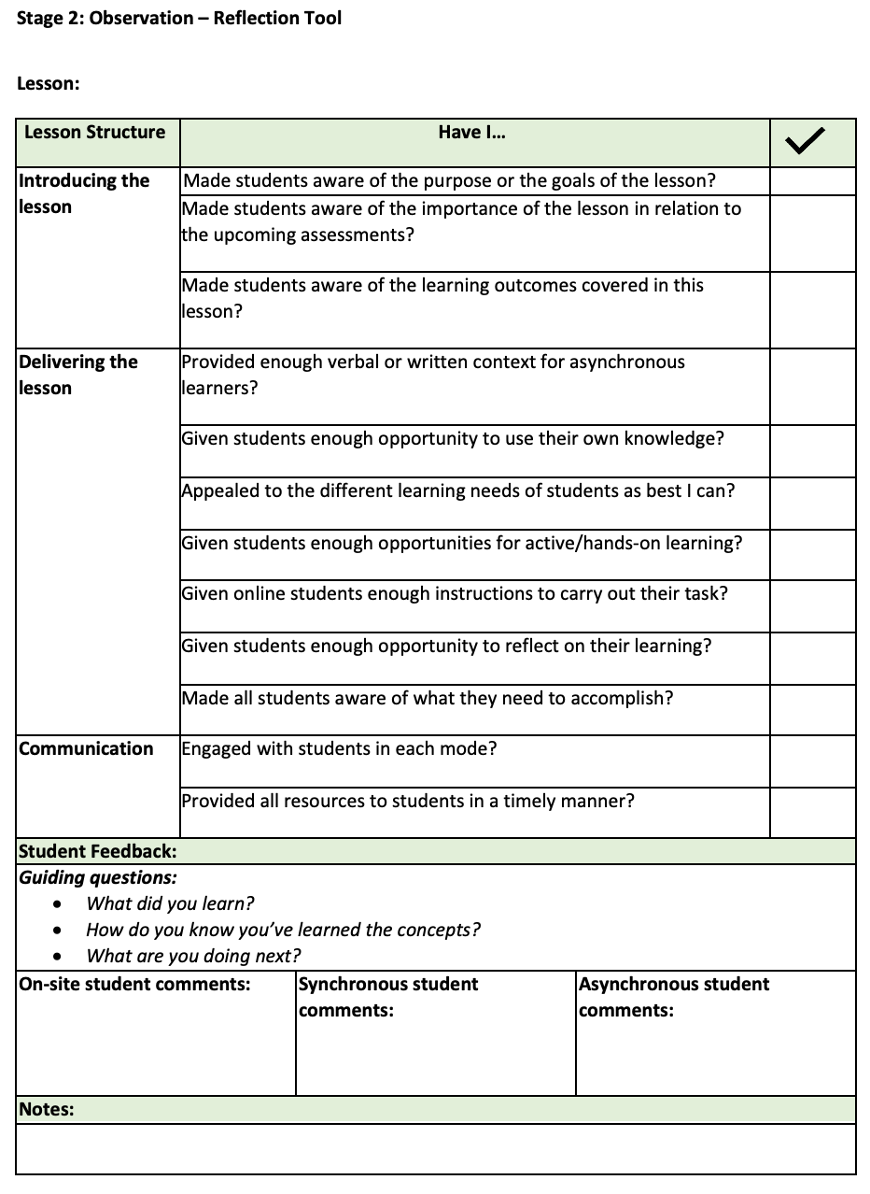

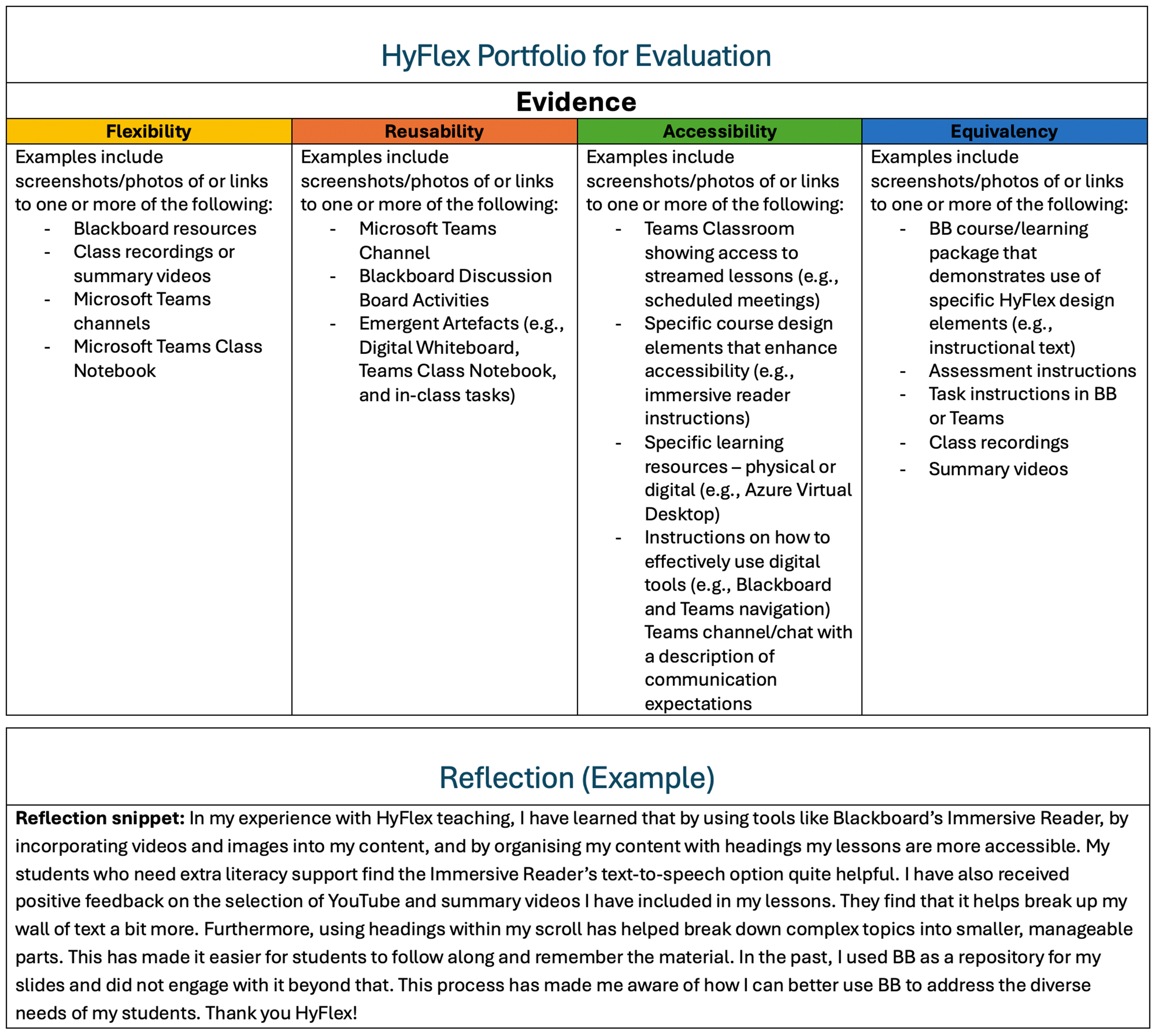

In those sessions, topics related to HyFlex course design and facilitation are discussed. Based on ID-reflections, analysis of their workload, and staff feedback, the instructional coaching process was pared back with fewer observations/debriefing sessions (i.e., at most three cycles per semester). Additionally, IDs recognised the need for greater emphasis on instructor goals and less on compliance monitoring. Observations tools that were originally adapted from Brinkely-Etzkorn’s (2018) work were further altered based on suggestions from the Screen Arts teaching team (Figure 4). Originally, IDs were responsible for providing instructors with the ‘how-to’ and ‘why’ behind specific HyFlex teaching practices, as well as assisting with technology-related issues. Now, much of the technology-support work has been shifted to other areas of IT (i.e., the HyFlex AV Engineer, IT HelpDesk, and the Application Support Specialist) to better distribute the workload and utilise expertise within the organisation. After two years of teaching in HyFlex (i.e., at least 4 semesters), instructors are asked to complete a HyFlex Teaching Portfolio (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Observation Tool

Figure 5. HyFlex Teaching Portfolio

Each year, IDs make conscious decisions to adapt the support system to better meet the needs of instructors and students. Rather than IDs being the main source of information on HyFlex teaching, instructors now have more options for accessing help and in a manner that they prefer. CoPs have allowed for sharing of strategies concerning emergent HyFlex-related issues (e.g., setting participation expectations). Incorporation of UDL and COI principles have provided instructors with a greater understanding of designing with a student-lens and what good online facilitation entails, respectively. And finally, by IDs evaluating instructors solely on their capacity to meet the principles of HyFlex, greater emphasis is placed on instructors’ HyFlex teaching abilities rather than on their ability to meet the goals set by their respective programme managers (PMs), which has been a challenge and will be elaborated on below. With these changes, a more robust method of supporting staff has been established; although, the system is under constant re-evaluation.

Implementation requirements

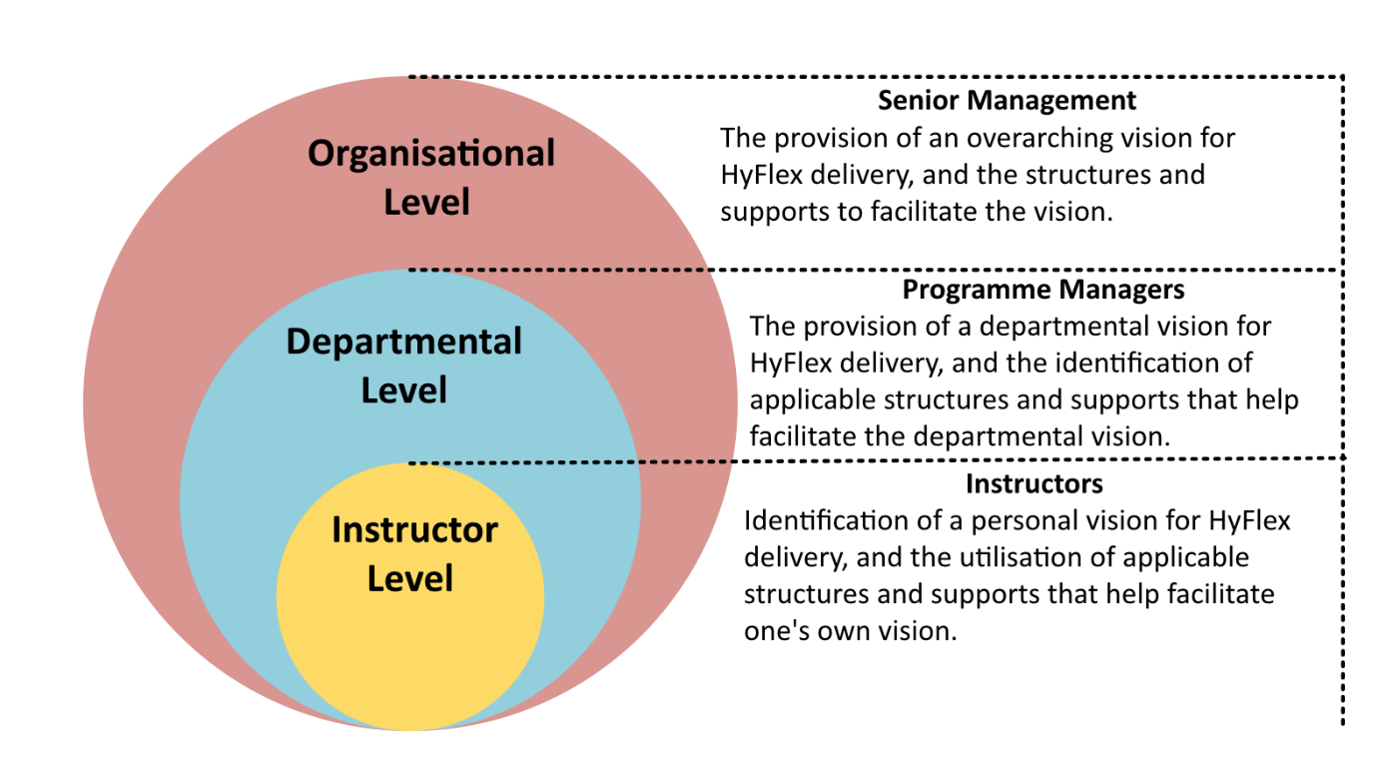

Figure 6. Summary of Roles and Responsibilities

Implementation of the support system has hinged on engagement from various stakeholders (i.e., senior management, PMs, and instructors) (Figure 6). With respect to the first, their role in the HyFlex project is to provide the overall strategy by clearly defining what HyFlex is, setting guidelines for participation, and adequately funding the project. This is in addition to the provision of appropriate structures (e.g., HyFlex AV equipment), and support. For instance, full-time teaching staff are expected to teach a maximum of 825 hours per year. Those involved in the HyFlex project are given a reduction in teaching load by 60 hours for every 15-credit course to be redeveloped. These development hours may not necessarily be spent solely on content creation, but on any form of in-house professional development related to HyFlex (e.g., IT training and instructional coaching). Furthermore, actual usage must be reported back to senior management. In terms of the support system specifically, senior management is to provide instructors with access to and time for it.

Although the framework for HyFlex delivery is determined by senior management, it is often the PM’s vision that is manifested. For them to be able to conceptualise what the delivery mode would look like in their department, they must be knowledgeable of HyFlex delivery, of their own context, and of the skills of their staff and students. Since most PMs involved in the project are also instructors, it has been found that they are likely to take the lead with HyFlex development and engage in various aspects of the support system. In doing so, they are better placed to direct staff members to help. In addition to development, PMs are also responsible for communicating with IDs’ team lead on what courses will be redesigned, in what order, and who will be responsible for them. In several cases, redevelopment of programmes that were deemed HyFlex appropriate by senior management stalled due to lack of PM engagement. And so, PMs have been essential in ensuring that support is utilised and plans appropriately communicated.

And finally, instructor involvement has been necessary in shaping the support system’s content and processes. Perspectives from all HyFlex instructors are frequently sought via survey and through one-on-one discussions with the latter being the more effective means of gathering information. Their views generally form the basis of ad-hoc workshops and CoP topics. Evaluation procedures are revised each year with the help of current instructors who are willing to either be test cases or to co-construct evaluation tools. What has been challenging is maintaining interest in the CoP and the self-paced course. Often, prompting and encouragement from IDs has been required.

What the support system entails and the challenges associated with it

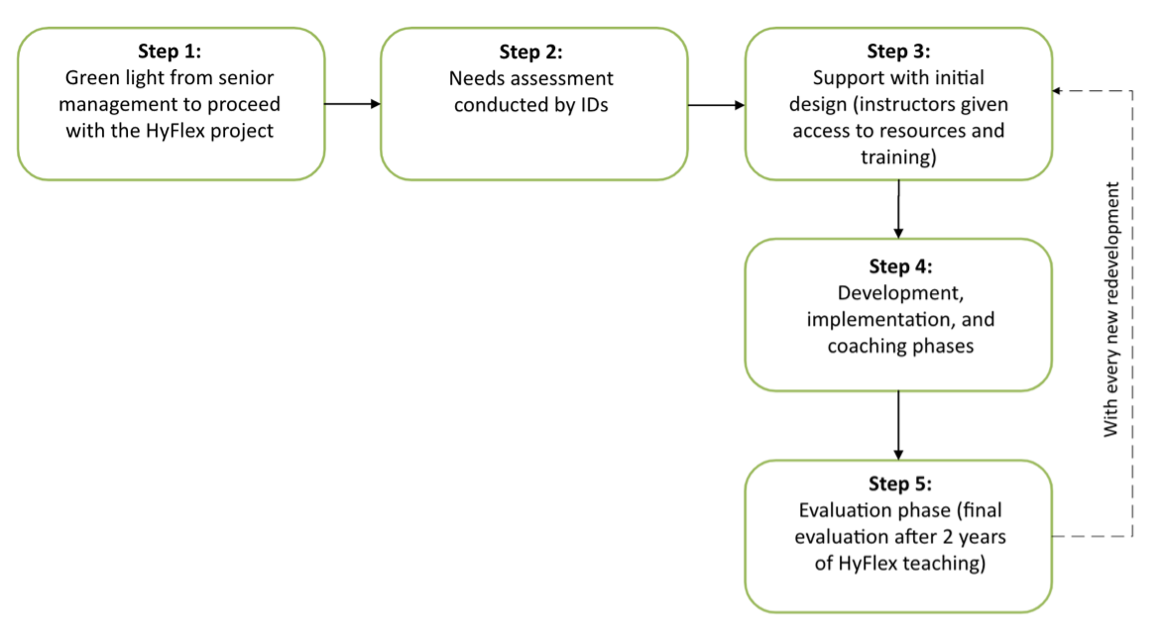

Figure 7. Onboarding Process to Evaluation

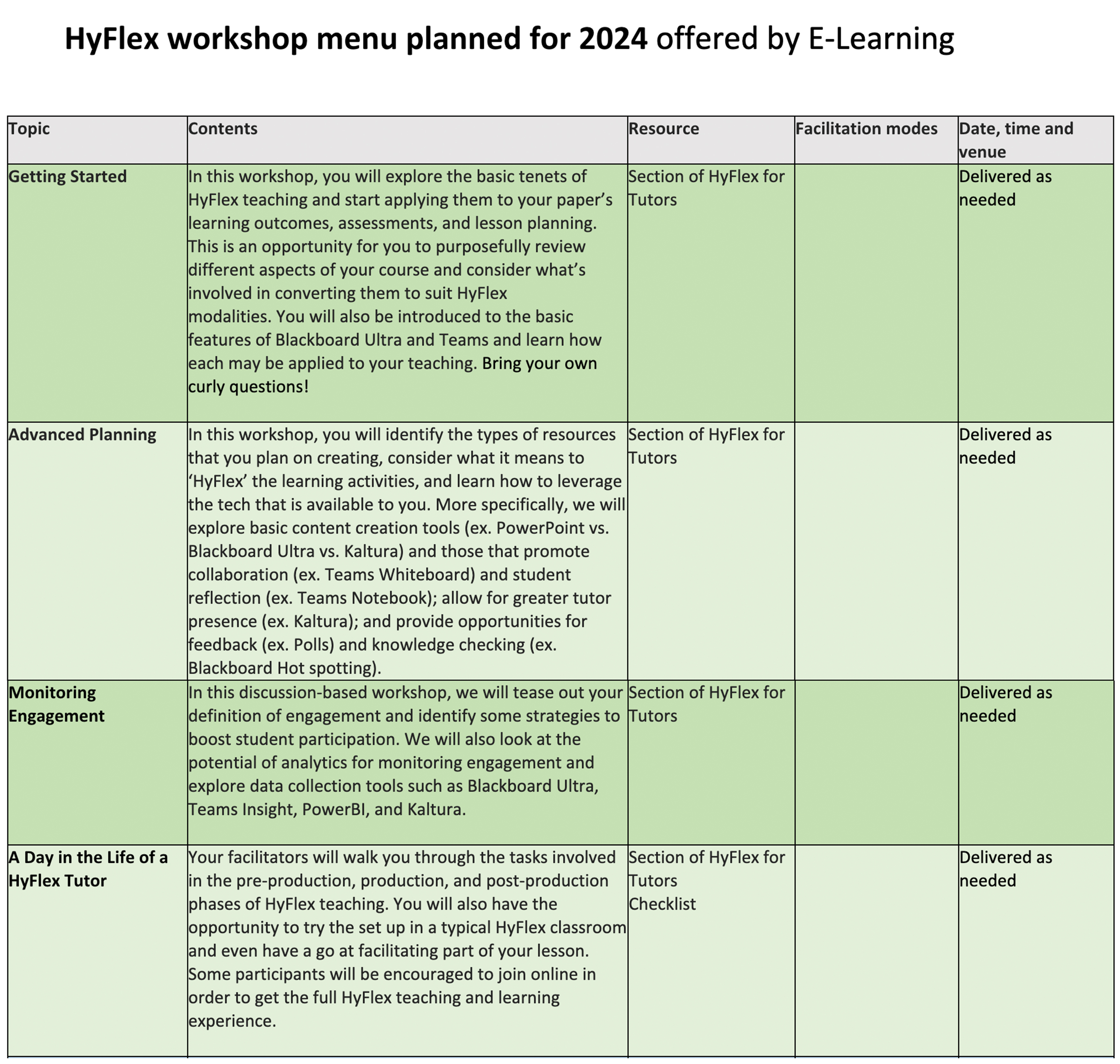

The onboarding process is systematic and requires input from PMs and instructors (Figure 7). Once PMs have expressed interest in the project and received approval from senior management to proceed, IDs make initial contact with them to discuss the vision, needs of the department, and approach to onboarding staff. Introductory workshops delivered in HyFlex are generally the preferred method and serve as opportunities for instructors to have a play with some of the tools they may be interested in using (e.g., Microsoft Whiteboard) (Figure 8).

Figure 8. HyFlex Workshop Menu Example

IDs then connect with individual staff who will be teaching in the upcoming semester for a meeting to discuss the basics around redesigning a face-to-face course to one that offers online participation; worksheets provided in the Hybrid-Flexible Course Design (Beatty, 2019) have helped guide these initial design discussions. At this point, instructors will have been granted access to both HyFlex for Tutors Blackboard course and associated Teams Classroom. Once instructors have an idea of what HyFlex would look like in their context, commencement and the frequency of coaching sessions is then negotiated. Lesson observations include IDs reviewing their online resources, viewing class recordings, and/or attending live sessions as in-person or synchronous participants with the intention of assessing the online student experience. During debriefing sessions, both instructors and IDs document strategies that have been successful and areas for improvement. Throughout the semester, instructor progress is shared with PMs. As mentioned previously, a final evaluation is conducted after two years of HyFlex teaching.

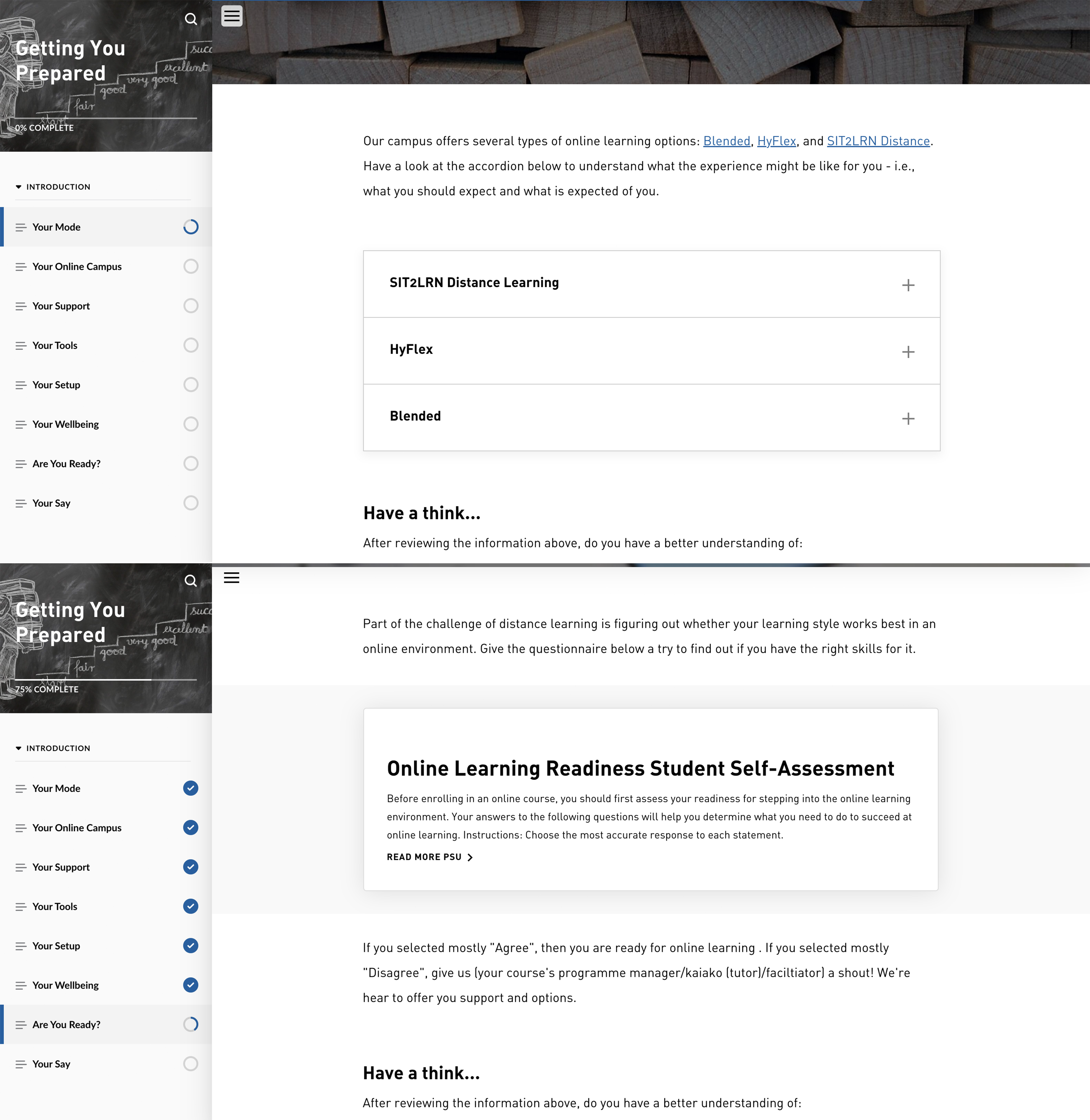

Several challenges have been identified with the support system. First, PMs have often struggled with identifying a clear vision for HyFlex delivery at the outset, which has made it difficult for IDs to determine the type of training required. At times, examples from within the organisation have not been enough and requests for field-specific ones are not possible. It is not until PMs have had at least one year of experience with HyFlex delivery that they are better able to articulate their vision. Second, instructors’ openness to be observed and to receive critical feedback has been difficult to navigate. Although this process is now optional, in the first few iterations, it was a core component of the support system. To address this problem, workshops on general teaching strategies (e.g., reflective practice) have been offered to all HyFlex instructors since many of the coaching discussions have revolved around this topic. Additionally, relationship building and encouragement from PMs have been necessary to ensure instructor engagement. Third, instructors have not always been compliant when it comes to completion of specific tasks (i.e., documentation of development hours and final evaluation process), which has required some persuasion from senior management. Fourth, navigating the boundaries of the PM-ID relationship has been difficult on occasion, especially around management of PMs’ HyFlex vision. In most of the challenging cases, IDs have felt caught between helping PMs “police” their expectations whilst acting as advocates for instructors. Siding with PMs has often resulted in a decline in the instructor-ID relationship. A contract system may be required to clarify the roles and responsibilities of each party (i.e., ID, PM, and instructor) in the project. In terms of asynchronous student engagement (the fifth challenge), successful solutions for bolstering participation have yet to be devised. Communication of instructor expectations of students, a description of what online learning entails (Figure 9), and the use of reflective tasks as a way for asynchronous learners to report on their progress are strategies that have been suggested and circulated within our community. Discussions around relinquishing control as a mindset change have also been conducted. It may be that outside perspectives are needed to help generate novel solutions, as not all instructors are satisfied with the degree of asynchronous engagement and the strategies proposed. Finally, IDs have made the link between instructors’ digital skills and the successful adoption of the delivery mode. What this support system cannot do and what should be addressed at an institutional level are the basic technology skills for teaching of all instructors. All-in-all, the system is not without its limitations.

Figure 9. Screenshots from the Getting You Prepared Module Provided to HyFlex Students

Impact of the support system

Over the span of two years, IDs invited new HyFlex instructors to share their perspectives on the support system. Of the pool of 20+ instructors, only four participants volunteered – three from the Faculty of New Media Arts, Business and Computing (Olivia, Ethan and Sophia), and one from the Health and Humanities faculty (Jackson). No compensation was provided to those who agreed to participate in the study. Involvement in the study included partaking in one-hour long pre- and post-support interviews, three cycles of lesson observations, and three one-hour long debriefing sessions after each observation. Pre- and post-support interviews were used to gather information on instructors’ perceived levels of preparedness while the other two strategies were used to ascertain changes in teaching behaviours. To protect the identity of the participants throughout the process, pseudonyms were used.

Methodology

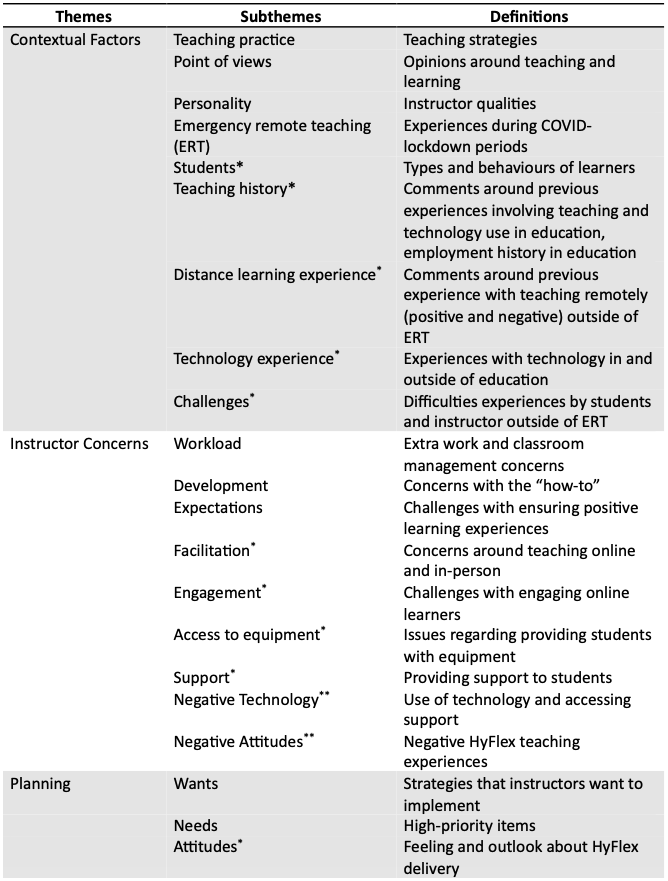

Instructor perceptions of their preparedness before and after the support period was addressed through comparison of themes identified from the analysis of pre- and post-support interview transcripts. Contextual factors, instructor concerns, and planning were identified as the common themes across the two time periods; although, positive experiences were identified as being specific to post-support interviews (see Table 1). Twenty-five subthemes were identified in total with nine of them common across the two periods; 10 subthemes were unique to pre-support interviews and six for post-support interviews.

Table 1. Pre- and Post-support Interview Themes and Subthemes

**Unique to pre-support

interviews.

**Unique to

post-support interviews.

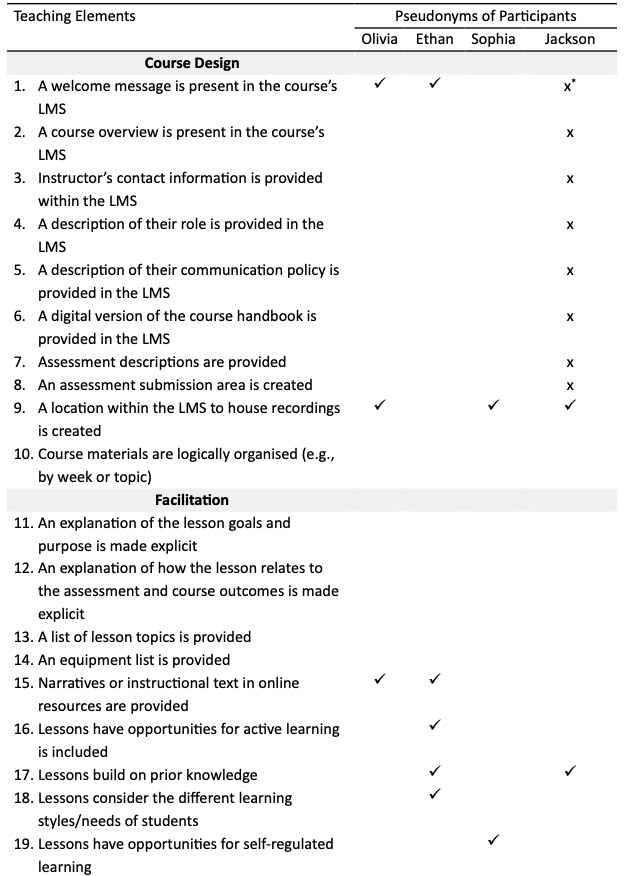

In relation to the observations, specific teaching elements exhibited by HyFlex instructors were monitored for and tallied to generate the four instructor profiles (see Table 2). The quality of one’s course design and facilitation were assessed in the first 10 and the last 14 items listed, respectively. Course design practices were considered ‘newly acquired’ if they were present in the latest iteration of the course, but not in previous offerings. Newly acquired facilitation skills were identified as those that were not displayed in the first observation session but appeared in subsequent ones; skills demonstrated from the start were not considered new and were assumed to be embedded practices.

Table 2. Newly Adopted Teaching Elements Pertaining to Course Design and Facilitation.

Debriefing sessions provided the opportunity for participants to disclose additional teaching behaviours that were not directly monitored for using the observation tool. Descriptions of each participant are provided below.

Olivia

Olivia is a highly experienced instructor with 20+ years in the field. She has taught in both face-to-face and technology-supported settings in the past and has participated in online classes as a student. Although she has had prior experience with the use of edtech tools (e.g., Blackboard, Collaborate, YouTube, PowerPoint), she does not consider herself to be technologically fluent. She initially described her practice to revolve around the use of PowerPoint slides and class discussions. However, after a single semester of HyFlex teaching, she reported a wide range of practices that she was able to employ such as instructional text (the “golden thread that blends it all together”) into her Blackboard materials, chunking of content, and the use of online discussion boards for all students. Although she prefers face-to-face instruction and values relationships in her practice, by making her teaching more visible in the online space, she came to recognise the power differential between herself and her students. This was in relation to supplying exam tips to those who attended:

“It was a little bit of power play. You know and I never thought about it that there's a power play”.

Olivia also noted the need to be brave with experimentation and acknowledges that she should have been braver sooner.

Olivia cited several issues related to HyFlex teaching. With regards to workload, this was initially described in terms of the time required to create interactive elements. Olivia later described this in relation to being able to sustain the pace of development in the face of constant updates to the content, and the need for more time and space for reflective practice. She also raised the concern over the expectation of technology “actually doing the job that I need them to do”; during her semester of HyFlex teaching, Olivia reported ongoing issues with the lack of sound while streaming videos. She also foresaw difficulties with facilitating discussions in mixed cohort situations and anticipated challenges with classroom dynamics should many choose to learn offsite:

“I'm a little bit worried that we're going to end up with just classes of international students because they have to be here.”

(Note: At SIT, international students are required to physically attend classes 100% of the time as per their visa requirements). Neither one was addressed in the post-support interviews.

Fewer needs and wants were described by Olivia post-support. She still intends on developing more interactive content; however, she did manage to create a learning community and incorporate the use of online discussions into her lessons. A new want that was borne out of her experience was a change in the classroom configuration; more specifically, the repositioning of the instructor presentation station so that she can view both her face-to-face students and those online. She initially shared the need to devise strategies for managing asynchronous student participation and to be cognisant of the online student experience. No new needs were disclosed.

Overall, Olivia reported positive experiences with HyFlex teaching. She stated that both she and her students have enjoyed it. In terms of the support provided, she valued seeing examples of HyFlex course development (“The opportunity to see what others have done is a powerful tool”) and commented on its authenticity compared to the support traditionally provided by the organisation. Although described in the interviews in some detail, Olivia was shown to acquire four new facilitation skills.

Ethan

Ethan is another highly skilled instructor with over 40 years of experience. Like Olivia, Ethan relies on PowerPoints and discussions to engage his students, and prefers face-to-face instruction. This was described as an easier means of facilitating debate, a technique that is integral to Ethan’s teaching:

“You know, you get people talking and involve groups, although it's not near as good online”.

He also reported on previous experience with Blackboard and Collaborate, and online teaching. He disclosed issues with engaging online learners during his ERT experience. Unlike Olivia, Ethan views himself as confident with technology. In his post-summary interview, Ethan described the want to experiment with a flipped-classroom approach to teaching and recognised the need to be competent with technology due to its dominance in the classroom environment:

“If you've got a HyFlex classroom, it doesn't matter how you're tutoring... everything depends on the technology”.

For Ethan, concerns pre and post support varied. Initially, his issues were around how to go about developing resources for HyFlex and the face-to-face student experience diminishing with greater focus on online learning. He also described potential difficulties with managing discussions when students are distributed. Technology concerns dominated his post-support discussion. For instance, he described the tedious nature of having to reformat content that was copied into Blackboard, and the on-going issue with streaming videos. He also mentioned the feelings of inadequacy when he could not address the technology issue in real time.

In terms of wants and needs, compared to Olivia, fewer were disclosed by Ethan. To him, it was important that he receive training on the “how-to” of development. He also expressed a positive outlook with HyFlex delivery and described confidence in managing it:

“I certainly don't have any feelings of stress about it”.

After having taught in that manner for one semester, Ethan described the want to change the configuration of his classroom, reminiscent to Olivia’s disclosure. Additionally, in terms of the workarounds he developed, Ethan mentioned the want to “know the right way going about”. According to him, his goal now is to “experiment more and not with the technology, but with what [he can] do in the classroom”.

Ethan also disclosed positive experience with HyFlex teaching. He mentioned the relative ease with acquiring technological skills. Despite ongoing technology issues, Ethan stated that he has “got faith in the technology”. In terms of the support system, Ethan saw worth in the practical sessions where instructors were introduced to various applications to support their teaching. Based on the lesson observations, Ethan has demonstrated to have acquired six new HyFlex facilitation skills (e.g., use of instructional text), which represents his greater awareness of the online student experience.

Sophia

Compared to the others, Sophia is least experienced with less than five years on the job. Like Ethan, she has previously taught online in an asynchronous capacity and feels comfortable with the use of technology. Sophia, too, relies on the use of PowerPoints and disclosed the importance of building relationships with her students; however, the provision of hands-on experiences is what sets her apart from the other participants:

“We’ll go out [and] we’ll do something”.

Although Olivia and Ethan articulated specific teaching practices, in her post-support interview, Sophia made general statements about obtaining greater awareness of what online student can do. Additionally, she noted that her ERT experience was good preparation for HyFlex.

Like Ethan, Sophia’s issues varied across the two time periods. Initially, Sophia was concerned about the distribution of physical equipment to distance students (“they [equipment] would probably cost a couple $100 shipped up”), which was unique to her situation. She also questioned how facilitation of discussions could occur seamlessly using the in-classroom equipment (“You couldn't be handing the microphone ‘cause you know it's fluid, the conversation thing”), how an inclusive environment can be established, and what supporting students with physical tasks in real-time would look like. Later, Sophia’s main concern was around the technology provided not being fit-for-purpose in her context:

“For a programme like mine, it’s too heavy and it doesn’t cope”.

In the case of needs and wants, Sophia only disclosed them in her pre-support interview. Sophia was one of the few to mention wants, which included the creation of video resources. In relation to needs, she disclosed the requirement for strategies to engage online students, access to physical equipment for her students, and a “uniform” or consistent structure to her online resources. Like Ethan, she, too, possessed a positive outlook prior to HyFlex teaching:

“At this stage, I actually feel really confident”.

In her post-support interview, Sophia mentioned several positive experiences. In terms of student engagement, she shared that students have been involved in discussions regardless of their participation mode. Sophia identified greater value in this form of support than what she had experienced in previous training opportunities. She described the latter as:

“You almost got to flounder your way through”.

She also saw value in the availability of the IDs. Although not explicitly mentioned in her interviews, IDs identified that Sophia had acquired three new facilitation techniques.

Jackson

Jackson also shares over 25 years of teaching experience. He, too, has experienced online study as a student, has used Blackboard and Collaborate in the past, and uses discussions as his main method to engage learners. Although not mentioned in his earlier interview, he disclosed use of PowerPoints in his latter discussion with IDs. Like the others, face-to-face teaching is his preference. He also considers himself to be a “luddite”. In terms of his ERT experience, he described issues with online engagement that was off-putting to him:

“Everybody would turn the microphone off... and a lot of people don’t put their videos [on] and they just, they’re just a little silhouette on the screen”.

Unlike the others, Jackson did not describe perceived changes to his teaching in his post-support interview.

As the rest of the participants, Jackson’s concerns also differed across the two time periods. Initially, his main worry was having the skills to adequately support online students:

“My main concern is something going wrong that I can't address and leaving people hanging”.

This then evolved, as described in his post-support interview, into struggles with finding the middle ground between the expectations set by his PM and his own way of teaching:

“We have to list exactly what we’re doing and I don’t always work that way”.

Like Ethan, the concern with looking incompetent in front of students when technology goes awry was true to him and continued to be so even after his HyFlex experience.

In terms of planning, Jackson disclosed the need for technology support and offered a more negative outlook compared to the others during his pre-support interview:

“I'm not gonna do this until I absolutely have to”.

In the post-support discussion, a new need was identified, which was to develop more online content. However, he failed to describe the specifics of it, nor did he delve into the pedagogy of HyFlex teaching.

Fewer positive experiences were reported from Jackson. When asked what he thought about his HyFlex teaching, his reply was:

“So I mean, I wouldn't say I feel 100%, but I don't hate it”.

He found value in the just-in-time support provided by IDs and for the feedback and reflection opportunities:

“It’s really nice to have someone you know whose there, if something goes wrong”.

Compared to the others, Jackson obtained fewer facilitation skills (two) and required greater real-time technology support during his live sessions.

Overall Findings

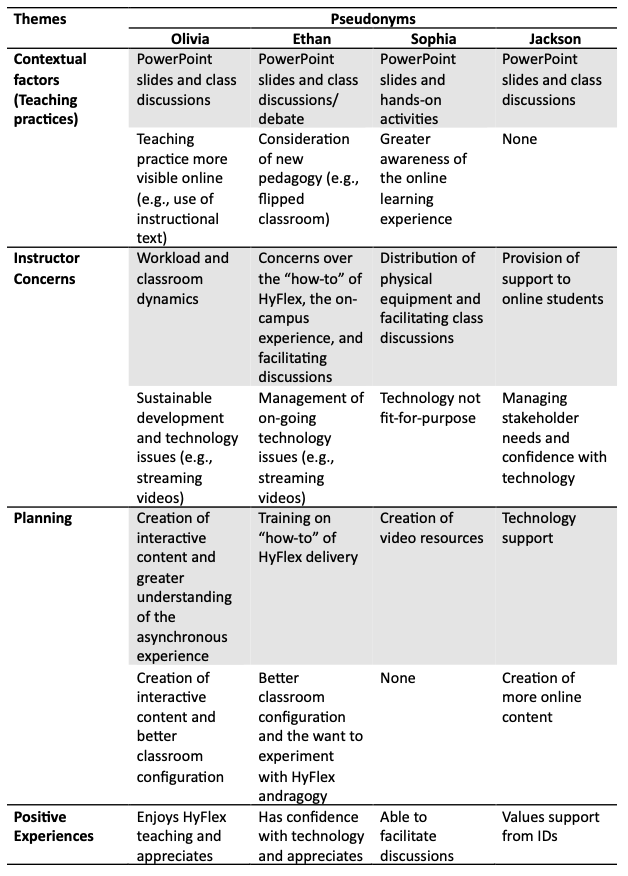

Table 3. Summary of Qualitative Findings

Note: Shaded areas denote perceptions prior to HyFlex delivery; unshaded areas denote perceptions after HyFlex delivery.

All instructors demonstrated some form of growth from the acquisition of technology skills to greater pedagogical-technological awareness. What can be surmised is that when the technology barrier is surpassed in that it does not hamper their ability to fulfil their teaching goals (or at least when instructors can operate within the discomfort of the possibility of technology malfunctioning) they are able to explore new pedagogical strategies. This is apparent with both Olivia and Ethan who noted that despite some difficulties with streaming videos, they were still able to engage the entire cohort with class discussions. As a result, they were able to move beyond the technology aspect of HyFlex teaching. For Sophia and Jackson, the technology barrier was far too great in that it impeded some aspect of their teaching; as such, it continues to be their main focus. Additionally, other than Olivia, most found it difficult to articulate their teaching techniques. This is where the lesson observations were of value, as IDs were able to recognise practices not disclosed by instructors. What IDs also identified was that there was little overlap among the teaching profiles, which meant that newly acquired skills appeared to be specific to each instructor. Taken altogether, all participants are now more knowledgeable of and possess greater skills in HyFlex delivery than they were at the start of the semester. This may be attributed not only to their proficiency and comfort with using technology, and their andragogical knowledge (as Olivia, Ethan, and Jackson are highly experienced instructors), but to different elements of the support system.

Recommendations

For institutions embarking on large-scale HyFlex deployment, it is recommended that the following be considered:

1. That there be options for support.

To enhance engagement, it is advised that a variety of avenues to access assistance is provided and that instructors are given the liberty to utilise the aspect of the support system that they see fit for their context.

2. That there be opportunities for peer evaluation, reflection, and practice sharing.

Observations and guided reflections may assist in identifying practices that instructors struggle to initially realise of themselves. Conduits for practice sharing would allow instructors to open their eyes to the possibilities of strategies that may be useful to them and be comforted in the fact that these strategies have been endorsed by their peers.

3. That digital fluency skills are addressed first.

To make the leap to HyFlex teaching more manageable, an institution-wide plan that assists instructors in building their capabilities to teach in a technology-supported manner is needed.

References

eatty, B. (2007). Transitioning to an online world: Using HyFlex courses to bridge the gap. In C. Montgomerie & J. Seale (Eds.), Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2007--World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications (pp. 2701-2706). Vancouver, Canada: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/25752/

Beatty, B. J. (2019). Hybrid-Flexible Course Design: Implementing student-directed hybrid classes. https://edtechbooks.org/hyflex/

Brinkely-Etzkorn, K. E. (2018). Learning to teach online: Measuring the influence of faculty development training on teaching effectiveness through a TPACK lens. The Internet and Higher Education, 38, 28-35. https://www-sciencedirect-com.ezproxy.massey.ac.nz/science/article/pii/S1096751616301889?via%3Dihub

Center for Applied Special Technology. (2024). About universal design for learning. https://www.cast.org/impact/universal-design-for-learning-udl

Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education model. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), 87-105.

Koller, B., Manuel, J., & Watt, K. (2023). A journey into the unknown: Reflections from novice instructional designers on identifying their place within the Southern Institute of Technology. Scope: Teaching & Learning, 12, 78-87. https://doi.org/10.34074/scop.4012003

Manuel, J. (2022, April 27). Navigating HyFlex: Upskilling staff and students [Conference presentation]. 2022 Anthology Digital Teaching Symposium, United States. https://youtube.com/watch?v=Dw2wJuzAHn0

Networked Learning Editorial Collective. (2021). Networked learning: Inviting redefinition. Postdigital Science and Education, 3, 312-325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42438-020-00167-8

Southern Institute of Technology. (2024). International FAQs: How big is SIT? https://www.sit.ac.nz/Home/FAQs/International-FAQs/ArtMID/7327/ArticleID/748/How-big-is-SIT

Universal College of Learning. (n.d.). Te Atakura. https://www.ucol.ac.nz/study-at-ucol/maori-pasifika/te-atakura