Chapter 3: Focus on Literacy

Scott shares this story about coping with his own reading delays: I had serious learning delays, likely caused from birth trauma. In first grade, I started speech therapy twice a week, with Ms. Button, the nicest person in my school. My dad helped me do the assigned exercises every day. I remember repeating the sounds exactly how I heard them and not understanding why people didn’t know what I was saying. But I kept trying, hoping to please Ms. Button and my dad. My parents were told I would likely always need speech therapy. I substituted d’s for f’s and w’s for r’s. My grandmother scolded me to stop talking like a baby. I also stuttered, putting me at a disadvantage compared to my twin brother who easily overshadowed me. When I was in first grade, I was one of three students in my class who couldn’t read. We were labeled as lazy or dumb. Each of us was punished regularly for various reasons. When I lost my place in reading, the teacher would call me up to the front of the room for a spanking, or if she was walking through the room, she would hit my knuckles with a ruler hoping that I would pay better attention.

Like most kids, I loved music. In third grade, I spent hours playing the Sears Silvertone guitar that I bought for $19.99. I listened carefully to records of the Beach Boys, The Ventures, Bob Dylan, and my dad’s favorite, Josh White. I spent hours in my room playing the records until the grooves were worn down, plucking each string on the guitar until it matched what I heard. My dad told me that when I could play Greensleeves, I would be a real guitar player. That song is still one of my favorites.

My careful listening eventually paid off. I remember the first time I heard myself speak accurately and realized that I was mispronouncing Fury, the name of the horse who always saved the day on a TV show. My dad helped me practice saying “Fury” instead of “Dewy.” It was as if a light went on. One day I couldn’t hear the difference, and the next day I could. I was elated. Now when I practiced, my speech actually improved. I worked hard and finished my visits to Ms. Button by the end of 3rd grade.

When I was in fourth grade, I was grouped with second graders for reading. I knew I was not a good reader, but I was shocked to discover how far behind I was. The humiliation negated any benefits I may have gotten from the reading instruction even though I knew I needed help. I thought about this situation and realized that the teachers did not know how to teach me to read, and I needed to figure it out for myself.

Then, something happened that changed the world. In February 1964, the Beatles debuted on the Ed Sullivan show. They were the coolest thing I had ever seen. I played my guitar and sang their songs. When I got the sheet music, I memorized what the words looked like off the sheet, as I knew them by heart. For the first time, I was reading words that were interesting to me. I would read the word and break it down to figure out what each letter said. I found the order of words, syntax, and sentence structure, and experienced how they interrelated in paragraphs. I had great visual memory. If I saw it, I knew it. I drew constantly, likely because I felt successful using visual memory. I developed the spatial reasoning to read chord charts and my ability to think and analyze was developed as I figured out chord patterns to transpose the Beatles songs I was playing into a key in which I knew all the chords.

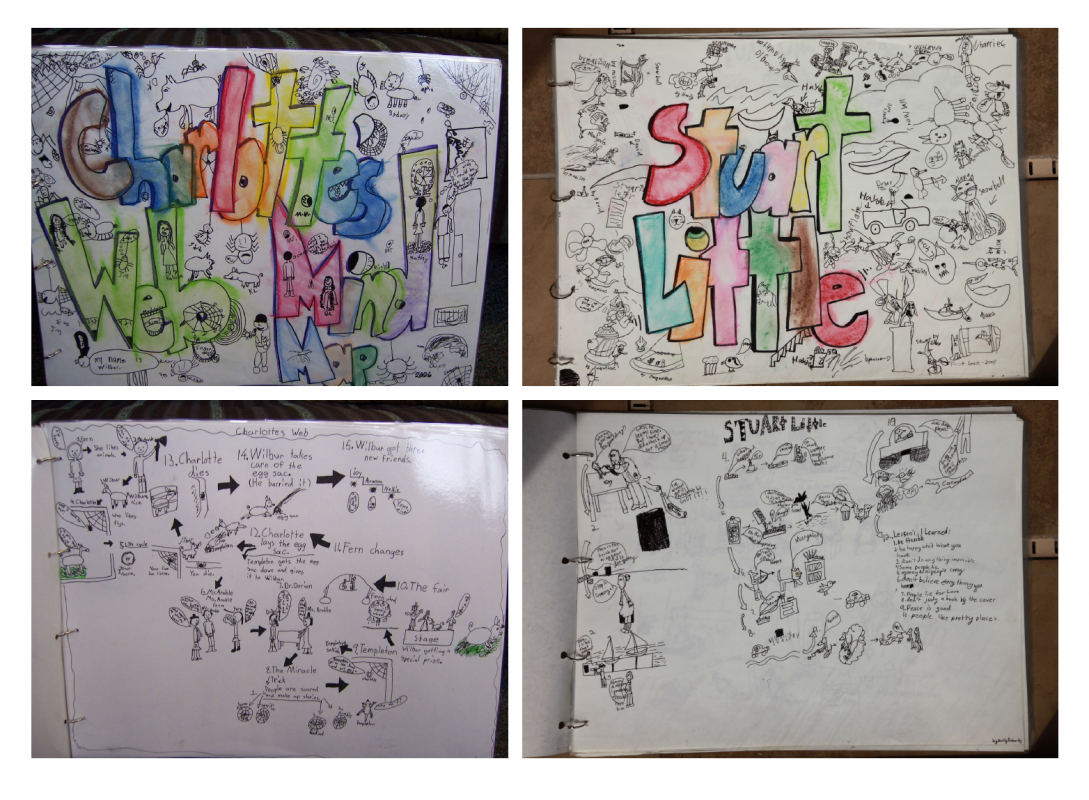

However, my vocabulary was still limited because until 3rd grade, I couldn’t clearly understand many of the words in the conversations around me. If I couldn’t decipher the words, I couldn’t conceptualize their meaning. I didn’t have a large enough vocabulary to use context clues, so I used images to compensate. The photos in the World Book Encyclopedia and the caricatures in Mad Magazine were a great asset, as I read the caption underneath each image and learned what the words meant. The satire in Mad Magazine about movies and TV shows deepened my comprehension because I had to apply higher level thinking skills before I knew why it was funny. The artwork in the facial expressions of the caricatures showed more than the dialogue, revealing inconsistencies in the caricatures, and reflecting their true thoughts and personalities. Laughing and discussing TV shows with my best friend while deconstructing the stories in our favorite magazine taught us to read expressions, identify details, make connections, compare and contrast, sequence ideas, make analogies, and understand irony. That is the experience I work to replicate when I use mind mapping to teach reading in my classroom. Children need an environment where their personal connection to the content drives their personal motivation to learn in an open-ended way. Over time, their unique neurophysiology will develop until their ability is synchronous with their age and they are able to meet external expectations.

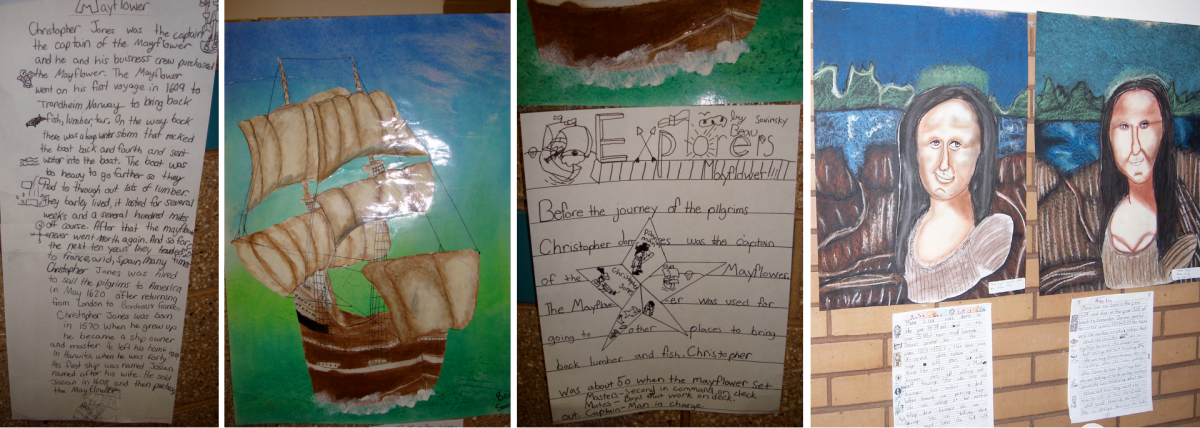

In sixth grade, Mr. Moynihan invited my band to play for the school dance and had me draw a timeline of the impact of European exploration on indigenous cultures for the classroom which he used for many years. He used my strengths in my academic learning and my skills and confidence grew. I was finally in the high reading group, reading and illustrating the Newberry books of my choice. This built my confidence, but it took years to fill in the holes in my reading skills.

Compared to the average student, I was large in stature and strong. I was successful in athletics, which saved my self-esteem. Through middle school, I played football and basketball and was the district champion in the shot put and softball throw. When I was in high school, I participated in athletics during the day and worked graveyard shifts at a plastic bag factory. One day, the foreman of the factory, an athletic ginger-haired man, pulled me aside and told me to stay in school no matter what so I wouldn’t end up like him. His message gave me the courage to take the high school remedial reading courses that I needed to compensate for my early challenges.

The guest speaker at my senior dinner was Mr. Moynihan. He remembered me as an artist and as an athlete who could throw. I knew that I was still important to him because he knew that I was a two-time state champion. I had a chance to thank him for using my strengths to help me be successful.

I started college on an athletic scholarship as a PE major and thought I would teach and coach. Breaking the college record in the shot put was the first time my dad saw me as successful instead of as a remediated student who always needed extra help. He showed up late for the track meet and missed the throw but was there for the announcement to see the standing ovation from the crowd. We sat on the bleachers after the event and talked for a long time, for the first time in many years. Seven years later, when he died, my mom found all my newspaper clippings still in his wallet.

My identity as a successful person was defined by athletics, but a few years later while taking education classes, I realized I also knew a lot about emerging reading skills. When it came time to choose a career, I knew I had a good understanding of how people learn, why they didn’t learn, and how to access what they were curious about. Having learned to read through self-directed experiences, I believed I could teach others to read.

When I started teaching reading, the available materials were limited. I selected materials that would have motivated me as a student and used that to teach reading. I used rigorous non-fiction reading materials with curious facts students want to learn more about, as well as high quality fiction to provide context from life experiences to make meaning about the information they learn. We read E.B. White’s books such as Charlotte’s Web, Stuart Little, Trumpet of the Swan, and others. As we discuss the life and death of Charlotte and the seasons on the farm, children at all levels, backgrounds, and abilities, engage their own values and experiences to achieve understanding, making connections to the non-fiction materials that provide needed background knowledge about farms, animals, spiders, and their own interests. I fit together a variety of strategies to improve learning readiness in physical and cognitive realms within an emotionally nourishing classroom.

We can see from Scott’s struggles that early intervention for reading challenges is key to a child’s success in school and life. Reading challenges are often a result of developmental delays that can be improved with daily reinforcement of developmental skills. Teachers need more training in developmental indicators to identify challenges and provide strategies to strengthen neurological processing, including visual and auditory processing, and fine and gross motor skills. When integrating basic drawing directly into reading instruction, a wide variety of student needs are met, including emotional,cognitive, and physical skills to help every child improve their capacity to learn to read well. (This proved consistent over 4 decades of students who regularly outperformed expectations: in low-income, high-income, and within a gifted and talented magnet program. The information about students discussed in this chapter can directly inform instructional choices. While ultimately it is the student’s responsibility to learn to read, it is the teacher’s responsibility to align as many factors as possible to support the student’s success.

Essential Elements of Literacy Instruction

Along with reinforcement for developmental skills, children need comprehensive literacy instruction every day that includes phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, oral language, comprehension, writing, and concepts about print. These skills can be woven throughout daily language arts instruction which includes shared reading with the whole class, small group instruction, independent reading, read-alouds, word study, and writing instruction. These literacy elements can be thematically interconnected when related topics are strategically selected. This augments mind mapping for learning, which will be discussed in chapter 5.

Below is a brief summary of each of the instructional literacy elements and examples of how they can be thematically interconnected using a novel. What the children learn through their literacy instruction can then lead to a culminating creative project, such as writing and illustrating a research book.

Shared Reading

Shared reading is the reading aloud of text as a class while engaging in classroom discussions that elevate thinking. The text is often one to two grade levels higher than the class average reading level. In shared reading, each child has their own copy of the text or reads from a shared copy visible to the entire class. The teacher can read aloud or call on students to read aloud. High-quality literature is best for shared reading because the characters are complicated and the stories engaging. The selected piece of literature should be read multiple times: aloud by an adult with vocal dramatization, and independently by the students, and together as a group, in various order.

The literature used for shared reading can serve as the axis for all language arts instruction. Differentiated texts can be selected from books that have been leveled to accommodate various reading abilities. Books on a selected topic, although at varying levels, provide the targeted background knowledge needed. Videos, stories, and articles are also selected to provide needed context and additional background knowledge. Even grammar and syntax are best taught in the context of a piece of literature. Writing and drawing activities can be inspired by the literature as well.

To build safety during shared reading, teachers must know the skills, ability and personality of their students and call on them to participate in ways that they can be successful. In an ideal situation, observers can rarely distinguish gifted learners from learners with special needs because each question is tailored for the success of individual students. The teacher can differentiate for individual ability by asking students to read aloud passages selected specifically for them. The teacher can read a sentence aloud and ask a student to re-read the sentence. One student can read the chapter title, while another reads a phrase and another, a paragraph. This is an effective strategy for setting up a child to succeed and feel successful in front of their peers. Asking questions that a variety of children can answer, such as, what did the title mean before you read the chapter compared to after you read? Everyone participates and everyone contributes in a meaningful way.

When introducing a book for shared reading, it is important to learn about the author. In fiction, one of the characters in the book often reflects the author. Reading biographical material about the author before you begin adds insight into the characters and the story. Ask the students what points they predict the author will be trying to make based on their life experience. Students will be able to read the information more critically when they consider the author’s bias, experiences, and intended audience.

During discussions about the text, students should be engaging in learning activities such as making analogies, compare and contrast activities, Venn diagrams, and other drawing and thinking strategies that will be described in Chapter 4. Engaging in topics such as irony and human nature also deepens the meaning for students. Irony evokes high-level thinking, while discussions about human nature and how the world works, deepen learning within relevant contexts. Chapter 5 will discuss how mind mapping extends these conversations that are part of shared reading with written and drawn components to propel deep learning.

Small Group Instruction

Small group instruction should happen daily to increase individual skills and monitor the reading level and comprehension of each student. Students are placed in small groups based on their current reading skills and cognitive ability to engage in appropriately leveled text. This is the time for building basic skills, i.e. phonics, tracking, grammar, as well as a time for building thinking patterns, i.e. making analogies, sequencing, forming key questions, converting specific details into concepts, visualization, and keeping kids curious. If a student's ability to think is above their reading level, being placed in a higher group can motivate a student to work harder and should be considered when placing students in groups.

High-quality leveled readers can be used for small group instruction to provide short books on many topics. Teachers can choose specific non-fiction topics aligned with the selected piece of literature to provide needed background knowledge in history, social studies, or science. This information is fundamental to understand the work of literature being read. For example, if the students are reading A Wrinkle in Time for their shared reading literature, teachers can select leveled readers about outer space, UFO’s, quantum physics, missing ships, time travel, mysteries, and other related curiosities. This is a simple and elegant example of how project-based learning includes literacy strategies and assignments that are linked to a larger thematic project applying knowledge and skills across disciplinary lines.

During small group instruction, a teacher tracks individual reading progress through selected assessments. Understanding the purpose and meaning of each assessment helps teachers apply the data effectively. For example, many districts use standardized tests to measure benchmark growth in specific skills. There may be a separate test for fluency and another test for comprehension, and another test for vocabulary development, but the tests may not relate the skills to one another. Although each item needs to be looked at independently, how the scores relate to each other is important. For example, context clues relate to vocabulary and both improve comprehension. One way to measure comprehension is the student’s ability to use or identify context clues because context clues relate to vocabulary. Vocabulary development will more closely align with comprehension than fluency, whereas fluency in many cases is not an indicator of comprehension. Cross checking the data reveals a clearer picture. For instance, a 3rd grade student may score at benchmark on fluency, while not understanding what they are reading. Or perhaps their comprehension is high but they are reading slowly in order to better process the information, resulting in a lower fluency skill.

Questions and observations during small group instruction help teachers determine what the data really mean for each student. A teacher can interpret the accuracy of the comprehension score by looking for evidence of how the student answers questions, retells with details, thinks abstractly, finds context clues, or uses analogies (or synonyms or antonyms). When students construct an analogy and show how they connect the two items through classification, the teacher can see their thought process and know if their fluency scores and/or reading ability correlates with their comprehension and understanding. Teachers can formatively assess each student on various skills and individualize instruction during daily small group instruction. Information connecting reading strategies used in small groups and visual arts integration will be provided in chapters 5-6.

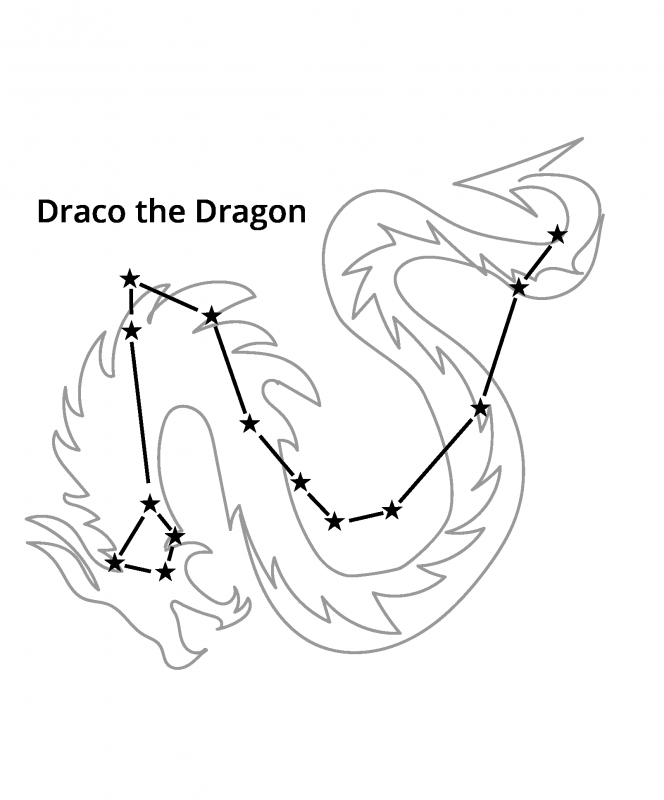

Making sure students are in the right reading group is vital. This requires the consideration of multiple data points, not just the assessment for reading ability. Student groups should be fluid and placements should be adjusted as needed over time. If students test higher on their vocabulary level than on their reading fluency level assessment, they may be motivated by being moved into a more advanced reading group. If a student is producing high-quality work but testing low, it is important they be intellectually stimulated by higher-level information until the reading level catches up. To understand disparities between fluency and comprehension growth, teachers should remember that some good readers are slow because they are processing deeply as they go. Some are afraid of making a mistake. Teachers who use the data as stars in a constellation will form a more complete picture through observation of student behavior, performance, and dialogue.

Each day the small groups read and discuss their selection and its accompanying comprehension component out loud (A-Z Readers work well for this). To extend the benefit, teachers could:

- Select leveled readers that provide background information, such as vocabulary and context needed to understand the piece of literature being read as a class during shared reading.

- Ask students to make analogies based on the topic they are reading about, and explain what the analogy is comparing, e.g. size, texture, classification, etc. For example, “The moon is like a silver plate because it is round and has a bright color.” Students can also describe how the analogous items are different, such as, “The moon is a sphere, and the plate is flat.”

- Make connections to math, including tables, graphs, and story problems. Help students identify important information and how they can formulate an equation or a diagram.

- Include literacy skills specific to social studies and science, such as the interpretation of charts and maps.

Independent Reading

Independent reading includes silent sustained reading at school or at home on assigned or self-selected content. Independent reading can be self-selected for pleasure, to pursue individual interests, or to gain needed knowledge. Independent reading can be used as a second or third close reading to augment information being read during shared or small group instruction. In Mr. Flox’s class, when reading a novel as shared reading, the students are assigned to pre-read passages from the selected book at home or to read related material. This prepares the students for deep thinking before the passages are read in class. Because the shared reading in class is the second reading of the text, increased comprehension and fluency are developed, and the class discussion helps students extract deep thinking concepts from the text. Students also need individual study time with the shared novel during independent reading to reflect on the themes being discussed in class, as well time to practice skills such as phonics, vocabulary, and thinking, and questioning practices.

It is difficult to supervise the quality of reading during independent reading. One strategy that can be used is to ask parents to read with the students at home and discuss the text with them. Parents often enjoy this which supports a culture of reading and discussing books at home. In the classroom, the children can select a topic and be put into groups. They can then discuss what they have learned about their topic of interest to promote reading for interest at school. This can additionally motivate students to research specific topics for reports and projects.

Teacher Read-Aloud

Another type of reading as a group is a teacher read-aloud. Read-alouds provide a pleasurable opportunity for students to relax, listen, and imagine the story while developing auditory processing and visualization skills for comprehension. The teacher’s voice inflexion and expressiveness can signify that something special is happening and heighten the sensory experience and engagement of the students. Consider reading by lamplight or using sound effects, props, and voices for each character. Read-alouds should be used regularly with various texts that are selected to build on the curiosity and enjoyment of the shared reading novel, or just for the fun and delight of reading or relationship building. Having the students draw during read-alouds may increase engagement and provide evidence about how the children are visualizing and interpreting the story.

Here, Scott shares a story of connecting with a former student through read-alouds: I ran into Ryan when he was 23 and had just submitted his application to medical school. He credited me for his excellent MCAT score because he had learned to love reading in first grade. He recounted how we turned out the lights, gathered on the rug and read Goosebumps. He remembered my weird theatrical voices and the thrill of the suspense. He said, “I had the confidence to try new things because you made everything fun. You showed me what I needed to know so I could figure out anything.”

Word Study

A vocabulary list on the board is a staple in most classrooms. Additionally, Mr. Flox has a list of Greek and Latin roots and their definitions. The roots selected support the vocabulary words. The weekly “test” covering the root words allows for class discussion as the students practice their test taking skills of listening and writing answers while digesting the meaning of the words. Teachers who work with second language learners emphasize the value of teaching Greek and Latin roots because students are often able to make connections with their first language and connections with the new vocabulary they are learning. For example, once they know ‘man’ means hand, (Spanish-speaking students will immediately recognize the connection because ‘hand’ in Spanish is ‘mano’), the meaning of the root illuminates the meaning of other words like manual, manage, manufacture, manipulate, manicure, manuscript, etc.

Students need to write sentences and paragraphs using each vocabulary word multiple times during the week. Students also build understanding when they illustrate a sentence that includes vocabulary words. Teachers can use 3-4 words in one sentence and in different contexts for deep examination of each word. The student’s drawings provide additional evidence of background knowledge and connections surfacing their individual understanding and perspective. Interweaving vocabulary practice throughout literacy instruction reinforces the meaning of words in different contexts. Each activity provides repetition in varied ways to add interest and novelty to the learning, which keeps the brain engaged.

Mr. Flox also asks the students to keep their own spelling list, called a word card, on a sheet of paper at their desk. When they ask how to spell a word, it is added to their personal list for future reference. The list is broken into alphabetized segments to organize the words. (See sample.)

To look closer at individual words as a whole, present the shape of the words as a sequence of blocks with one block per letter. Children then match the shapes of the words as different size blocks to the words on the vocabulary list. While doing so, children identify each letter while looking at the whole word (see sample). For practice in visual tracking and word recognition, use a word hunt where the words only go horizontally left to right.

Writing

Students will never write at a higher level than they can read and understand the vocabulary, but they can express ideas beyond their initial ability if additional tools are added into their writing activities. Writing is hard work and having new ideas to express is a key motivator to do that work. Ask students to add icons, images, and drawings to their writing. This helps students visualize words and new ideas to develop their imagination so they can see a story unfold in their mind.

The key to strong writing is the pre-writing activities. Many class activities, such as drawing an illustration, are designed to spark the imagination, activate emotions, and diversify thinking before the students are asked to write. A conversation about a work of art using the reading concepts provided can also organize and inspire ideas to prepare students to write. Ask students to write about selected images and paintings as they break the work into its component parts. Provide a writing component to every work of art created in class by students. Providing the students with background knowledge throughout the shared reading, guided reading, read-alouds, word studies, videos, and class discussions, combined with direct instruction on writing structure, allows for students' writing to be much more meaningful and fruitful.

Literacy across content areas

Reading and literacy are intertwined into every subject. Literacy is the process of reading and comprehending any text by breaking the text into component parts and constructing meaning from it. So, essentially, every teacher of any subject is a reading teacher. Reading at all levels includes developing essential vocabulary for new topics specific to the content.

Reading printed text is one form of literacy. Math literacy requires reading and making meaning of numbers, equations, shapes, charts, diagrams etc. Students can also be literate emotionally – by understanding their own emotions; socially – by reading others; or culturally – by being street-smart. Literacy in the art forms involves being able to use an art form to express an idea. A dance, a play, a piece of music, a work of art, a map, etc., are texts that are read and understood by looking at the component parts and discovering how they are interrelated to create meaning.

For example, the following key ELA core reading strategies designed to deepen meaning are easily taught while creating/viewing works of art:

- Ask and answer questions

- Determine the theme or central message

- Paraphrase

- Summarize

- Visualize

- Determine point of view

- Consider your own point of view

- Describe the characters’ traits, actions, motivations, and emotions

- Tell why the author/artist chose to make the characters the way they are

- Compare and contrast facts, themes, settings, and plots

- Read and comprehend a story

Visual art is a powerful way to teach these concepts and is one of many reasons every child needs visual art instruction.

Pulling it All Together

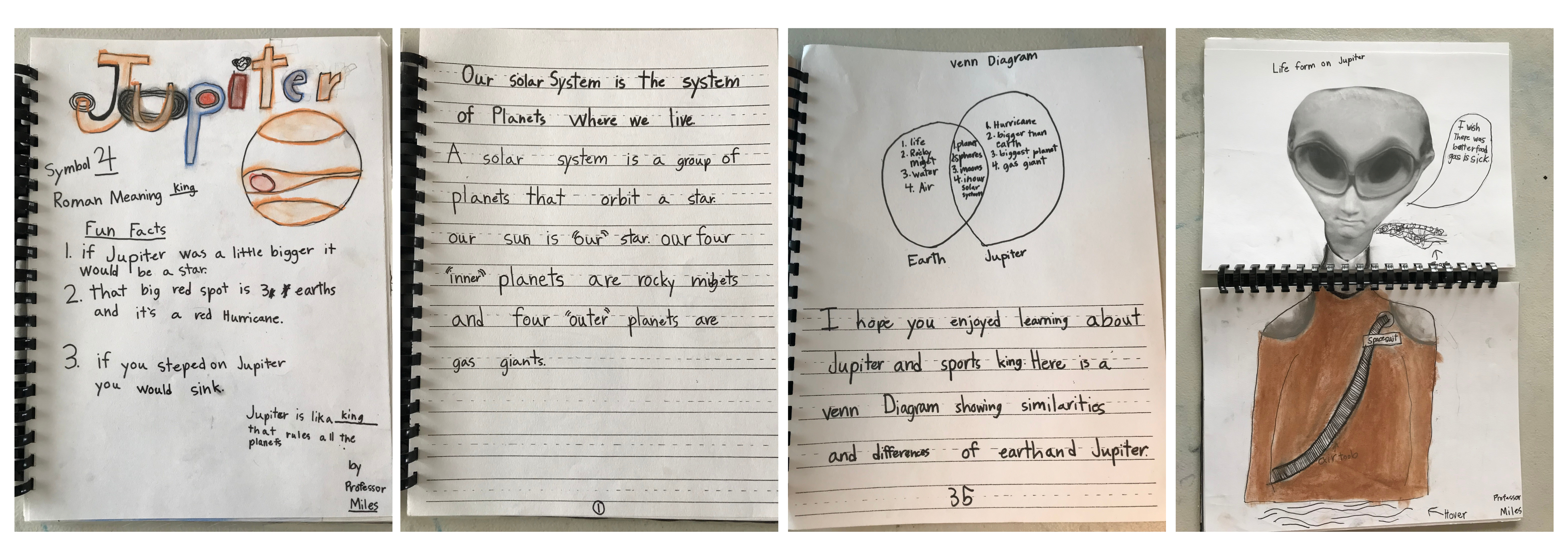

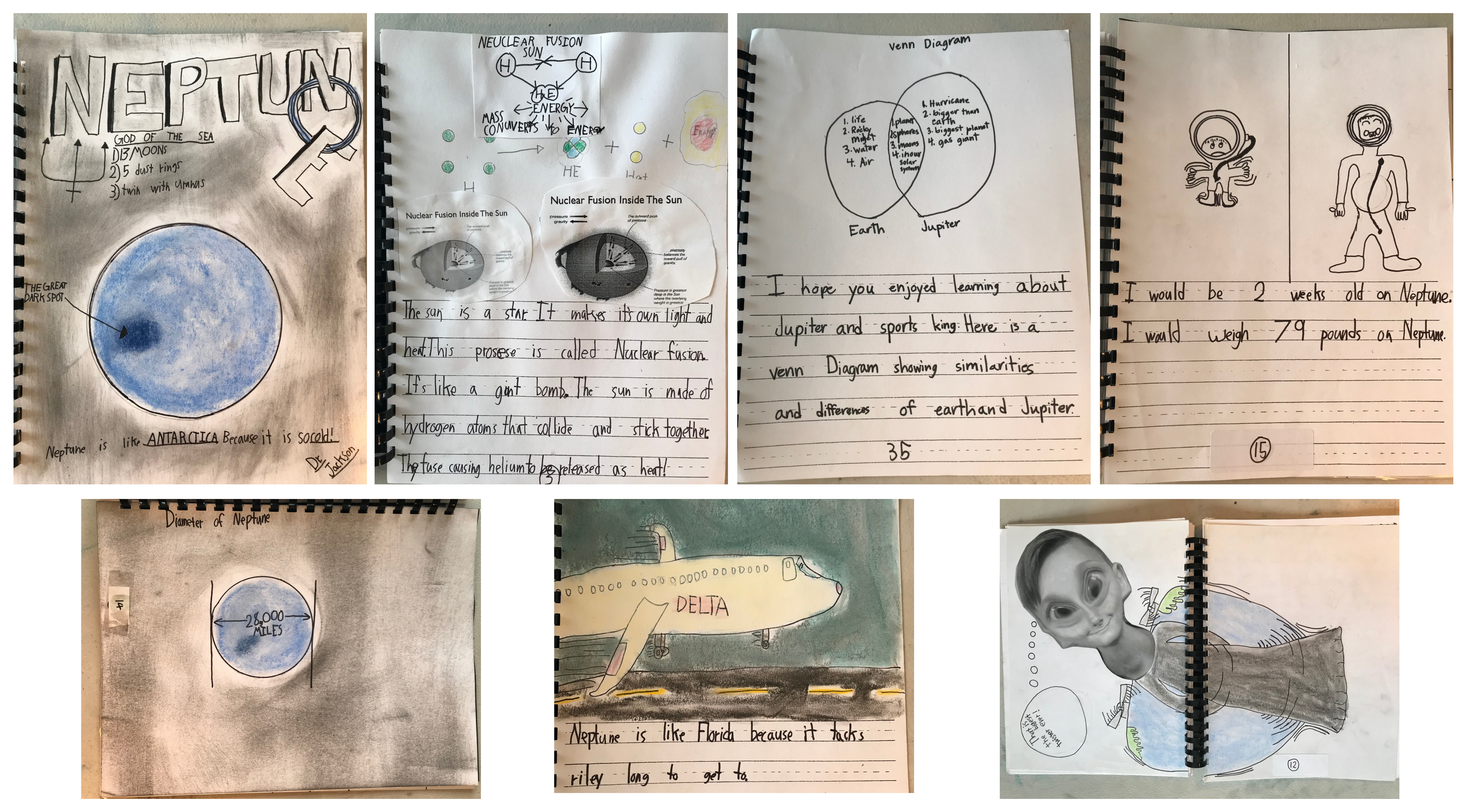

It’s important that students have opportunities to combine and put these skills to work in a practical application. One way to do that is through creating research books. Mr. Flox’s students, including the first graders, wrote two research books between January and May. He used topics from the required social studies or science core standards, selecting ones that excite children, capturing their interest while building skills in many of the required ELA standards. Below is a glimpse into guiding an in-depth research project about planets. Making a planet book takes a 4-6-weeks to create a 15-25 page book, depending on how many illustrations and diagrams the children include. Each step is done together as a class with direct instruction and student work happening simultaneously. Examples of student work can be found online at scottflox.com. Here is how it works:

Part One: Gather Information

- Display books with real photos and diagrams of planets around the classroom.

- Watch the video “Patrick Stewart Narrates: The Planets” to teach the students to take notes and how to make an outline for their book.

- Students brainstorm questions which are written on the board in outline form, starting with fact-finding questions on all 8 planets: the mass, the rotation, the size, distance from the sun, diameter, the elements the planet is made of, and the environment.

- Enthusiasm peaks when we take a field trip to the local planetarium.

- Students now have enough background information to select one planet for their report. Give them a few days or a weekend to select which planet they would like to write about.

- Write their names and the planet on the board so they can all see their name and planet posted.

- Gather students who are writing about the same planet to collaborate if they want to.

- Students can search the internet for additional information. Have them select the most important information and print it out.

- The teacher can provide charts and tables about the solar system.

- Students can bring additional resources from home.

- Students add the resources to the notes they have taken and are prepared with an abundance of reference materials to begin writing their report.

Part Two: Narrow the Focus, Extend the Thinking, and Create the pages

- Students and teacher refer to the list of questions. Teacher extends the questions moving from facts to higher-level thinking on Bloom's taxonomy: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create (Benjamin Bloom, 1956), as exampled below.

- Each page of the book answers one question with sentences, 1-2 illustrations, and diagrams. Possible questions include:

- What is the name of your planet?

- Why do you think it was named that?

- Describe what it looks like through a telescope.

- What does it mean in Roman mythology?

- Where is your planet in the solar system?

- How far is it from the sun? How far from the nearby planets?

- What elements is your planet made from?

- What is the diameter of your planet?

- Calculate your age in years if you lived on your planet, based on number of trips around the sun.

- Calculate your weight on the planet, based on gravity.

- Imagine and describe an alien that could survive on your planet. What adaptations will the alien need to survive?

- Describe the habitat of the alien and why the habit is effective on that planet.

- Illustrate the habitat.

- Make an analogy about your planet and illustrate it.

- For the culminating activity for their planet research, students get to be creative. Students create a life form that could live on that planet describing their food supply, shelter, life cycle, daily life routine, and physical characteristics.

- The students then support their ideas by making a chart labeled with three columns: facts, adaptations, ramifications, to explain how and why the life form lives and survives the way it does.

Part Three: Apply the Learning Through Creativity

- The final activity in the research book assesses what they have learned with a creative application. Students imagine themselves as a science professor who recently discovered a new planet.

- They draw themselves as an 80-year-old retired professor with a biography that they create.

- They then write new pages for their research book, answering all the same questions as the report on the first planet, describing their newly discovered planet. Students draw at least two illustrations per question writing dialogue as needed.

- The teacher serves the “professors” as a consultant to support their work.

- The students present their scholarly publications at parent-teacher conferences or to a fellow colleague in the class.

Reflection

- What are your best strategies for teaching literacy?

- What makes learning fun for you?

- Why did you decide to become a teacher?

- What talents and skills do you bring to your classroom?

- What empathy and insight about your students have you gained from challenges in your life?

- What do you value most about learning and schools, and how can you apply your values to increase your motivation?

Want to Know More?

Search for and read about Bloom’s Taxonomy, Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, or other theories to inform good questions.

Recommended Leveled Reading Materials: A-Z Readers RazKids, Reading Rainbow, and ReadWorks.

A terrific book for parents and teachers is The Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction by Megan Cox Gurdon.