Chapter 5: Create Mind Maps for Learning

Scott shares an experience illustrating the value of weaving literacy elements (chapter 3) and art elements (chapter 4) into mind mapping to optimize learning: It was mid-October, and my 3rd-grade class was studying the eye. We had read about the eye, watched a video, engaged in conversations, and each child was now building a mind map about the eye to demonstrate what they had learned. For the first time that year, every student was fully engaged in creating their work for over an hour. Each student was working on their own map, at their own pace, while incorporating their own ideas.

Emily was a shy child with an innocence that was accentuated by her buck-toothed grin. She was receiving treatment for delayed verbal skills and was two years below grade level in reading. Her visual perception and hand-eye coordination were competent so drawing her ideas in her mind map allowed her to express herself beyond her vocabulary, which motivated her thinking.

Emily’s deep thinking was visible in the pictures, words, icons, and emojis scribed on her paper and in the inspiring analogies she included. Her eyes sparkled as the ideas ignited and the images emerged. The concluding element of the mind map was to create an analogy about the eye. Emily quietly read to me her analogy at my desk. I knew she had reached a pinnacle of clarity in her ideas. I read Emily’s analogy aloud to the class, “The eyes are like a guide to show you the way.” Emily had exceeded my expectations, but more importantly, she had exceeded her own.

A critical mistake of the remedial reading instruction I experienced as a child was that the content was over simplified and uninteresting, which caused me to get further behind. I needed the intellectual challenge of ideas that sparked my interest to propel my intellect and capture my concentration until my ability to read could catch up. I could still think at high levels, it was my reading skills that were delayed. I started using mind mapping with fiction and nonfiction text, along with rich daily conversations and analogies, to inspire individual children to demonstrate what they were thinking in broadly differentiated ways.

The stage for Emily was well prepared based on a few foundational principles specifically developed to lead students to successful learning: she felt safe and valued in the classroom, drawing was improving her neurophysiology, conversations elevated her thinking, and clear learning outcomes drove the learning activities. Children like Emily are often discriminated against by current assessment strategies. She was previously unable to demonstrate her thinking because her vocabulary was limited, and her writing skills were low. But after six weeks of participating in a classroom that used mind mapping, she was beginning to trust her own thinking, and her ideas were evolving in complexity. Because of the open-ended questioning strategies, Emily gave successful responses repeatedly and her confidence developed. She was able to tell the teacher what she knew instead of trying to remember what the teacher wanted her to know, as she was previously conditioned.

To help children like Emily, teachers can read the children through their behavior, track their growth through data, and see the effects of the changing neurophysiology as they learn to see and to draw. Tony Buzan’s Mind Mapping book provides a strategy to see and track how students are thinking as they process information and provide clues to understand how they both assimilate and extrapolate information. By adding conversations while mind mapping, teachers can also inform the evolving thought processes of students. Using Bloom’s taxonomy to create questions and activities at each level, teachers can help students move toward the highest category of thinking, which is creating.

As students develop their mind maps, their thinking exceeds their ability to read and write as they draw and use symbols, emojis, and icons to extend their message. The greatest motivator to improve reading and writing is the drive to express complex thoughts and ideas. Students should always be thinking and conversing beyond their reading and writing ability. Mind maps and the conversations about them extend traditional thinking for students to excel beyond any preconceived expectations. This ability to express oneself beyond words is part of why the arts build deep thinking capacity. Mind mapping can activate this powerful concept from the arts into learning in all content areas.

Think and Learn Like an Artist

Arts learning can lead to effective and engaging project-based learning as students create a dance, music, play or painting. This learning is visible, relevant, and individualized. Mind mapping is a venue for all content to be experienced through project-based learning. When teaching through mind mapping, teachers and students work and think like artists. Each time a student creates a mind map he/she is producing creative work, just like an artist does. A classroom becomes a studio for hands-on learning represented in an artifact and students describe and discuss what they are learning. The instructional pedagogy for mind mapping is similar to the pedagogy for teaching visual arts. The essential components of a visual art classroom are present. The majority of the time is spent with students working on a project; the teacher provides instruction and background knowledge; there is reflection and critique throughout the process; and there is a finished product at the end for exhibition. (See Studio Thinking: the real benefits of arts education listed in the “Want to Know More?” section at the end of this chapter.) Each mind map is unique and reflects the individual’s learning. Discussing the map with another person provides an opportunity for them to review and teach what they have learned and to reflect on their work.

Artists explore and test solutions through trial and error. Then they carefully refine high-level techniques and use those skills to improvise ways to communicate new ideas. When a teacher teaches with mind mapping, they are also improvising to find the best solutions and refining instructional strategies, including the art of questioning for meaningful conversation. Teachers use their own judgment and perspectives to teach each individual effectively. Likewise, students also refine their thinking and develop techniques to communicate original ideas. Ultimately students have a visual artifact as evidence of what they know and can do. There is an intrinsic reward as they discuss their mind map with their teachers, parents, and friends, nurturing an authentic desire to learn.

As an artist’s skill increases, the level of detail and the nuances of the message often increase. Likewise, a mind map surfaces the nuances of thinking. It takes a basic web or graphic organizer, in which ideas are organized on paper in a visual format then adds content and learning standards made visible in drawing and notetaking to propel the visual artifact into a tool for divergent thinking, reflecting deeply, analyzing information, improving comprehension, and building personal relevance for the learner.

The activity of mind mapping is differentiated to meet the needs of advanced students, emerging students, and students with learning challenges in various situations. For example, in a mind map, second-language learners can express advanced ideas with images and use words in the new language as labels. Students with learning challenges compensate by developing alternate communication strategies in areas of strength to convey ideas. Gifted learners are motivated to extend their thinking and develop alternate ideas. Students will differentiate their own learning when they have access to many topic-related books and resources in the classroom.

Mind Mapping for Learning

Mind mapping for learning includes curricular standards and strategic questions to guide learning towards desired outcomes. Teachers can use mind maps to teach and assess basic facts and proficiency in core standards. The illustrations, icons, and graphic representations extend thinking beyond the student’s reading and writing ability and help develop abstract ideas. The learning is extended infinitely, as each piece of information becomes a building block to the next set of questions, continually spiraling upward. The student’s mind map is a culminating artifact that provides evidence of good teaching and student learning.

To summarize, mind mapping for learning is:

- A practical format for quality instruction and assessment adaptable for every classroom, preschool through adult.

- A strategy to differentiate individual learning.

- A practice to propel thinking beyond student capacity to read and write.

- An experiential learning process that activates imagination, emotions, and open-ended connections.

- A written representation of ideas that includes words, pictures, symbols, icons, charts, diagrams, labels, dialogue bubbles, illustrations, associations, characters, analogies, thoughts, and more.

- A conversation between a teacher and the students.

- A template to teach and assess higher order thinking every day.

- A formative assessment to inform a teacher’s instructional decisions.

- A summative assessment for a student to demonstrate what they know.

- An excellent review of material to prepare for standardized tests.

- A strategy to illuminate a broader range of skills than is currently being assessed in most classrooms.

Why does mind mapping for learning work?

Mind mapping is an effective tool for learning because:

- It provides evidence of student learning that students can describe and discuss.

- It rewards self-directed learning, independent thinking, and choice-making, allowing each student to connect with the prescribed curriculum in a personalized way.

- It applies Bloom’s taxonomy, teaching basic skills that lead to higher order thinking skills, culminating in creating a product.

- It applies and improves visual literacy.

- It allows teachers to incorporate their own strengths and personality into their classroom.

- It allows teachers to personalize instruction to each individual as they build relationships with students.

- It provides an immediate feedback loop with individual students.

- It illuminates the deep thinking of students as they discuss and describe their mind map to peers, teachers, and parents.

- It activates divergent thinking, invites creativity, and increases the number of related ideas leading to broader contextual understanding.

- It activates convergent thinking as students describe specific ideas from the curriculum.

Activities to include in a Mind Map

Each activity listed below should be taught explicitly in various types of lessons, including guided and shared reading, as well as being taught and applied in a mind map.

- Draw, illustrate or use icons, colors, shapes, symbols to depict ideas

- Summarize, paraphrase, describe, and sequence events

- Make lists

- Make a table to compare and contrast facts and ideas

- Identify cause and effect

- Draw tables charts, graphs, and diagrams, including Venn diagrams

- Write relevant mathematical equations

- Describe what happened

- Predict what might happen next

- Add photocopies of artifacts such as inventions, uniforms, weapons, strategy maps, and label each image

- Add dialogue bubbles

- Draw arrows for sequencing

- Include printed photos or images

- Deconstruct images with labels and descriptions

- Add analogies, metaphors, and ironies

General Sequence for Mind Mapping:

- Put the topic prominently on the page

- Add a representation of the main ideas, characters, or events

- Indicate what happened

- Indicate the significance or the impact of what happened

- Indicate why you think it happened (purpose and context)

- Indicate a personal connection or relevance to your own life

- Include a connection to the future and/or to the past

- Add an analogy

The weird and wacky things in history and life are essential for engagement and should be included in the conversations while mind mapping. Find the odd stories from the fringes that add interest about what happened. Identify the ironic twists and turns of fate. Finding and discussing the irony introduces ambiguity and drives deep thinking. It is the weird and the wonderful that keeps learning fresh and inspirational.

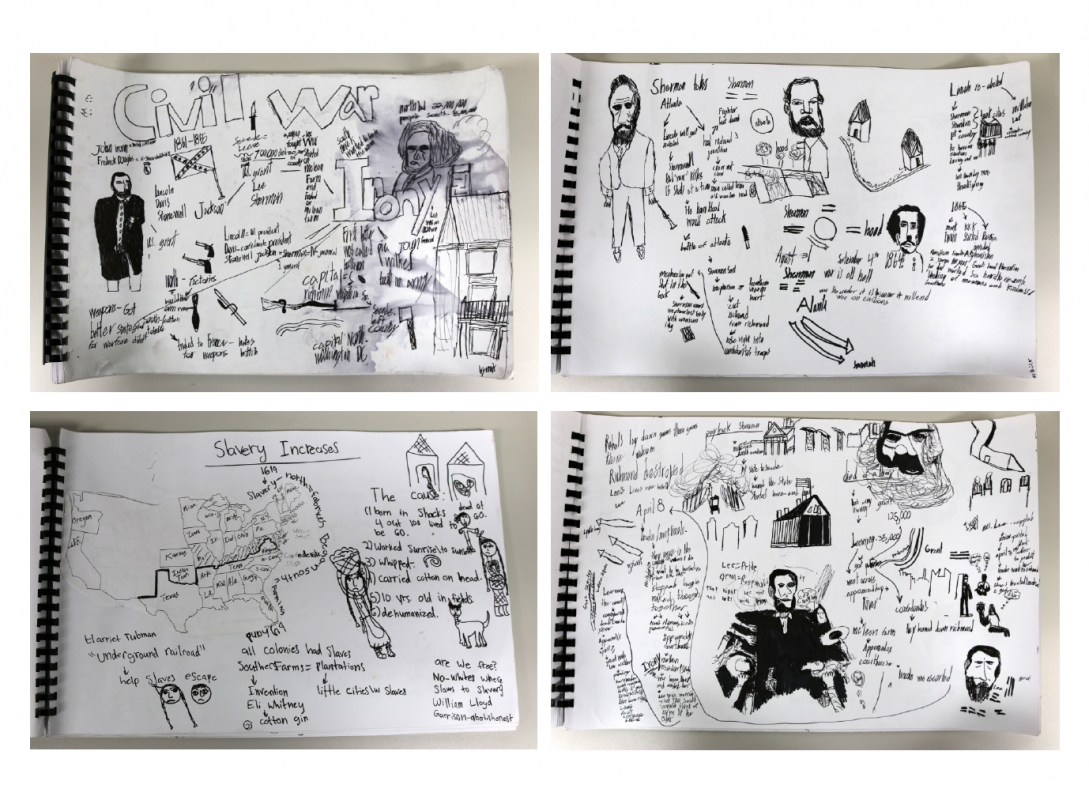

For example, when studying the Civil War, the 3rd grade students in Mr. Flox’s room create 20-30 pages of mind maps about the war and related concepts. The students remember particular details and recant the stories to classroom visitors. Favorite facts include happenings that are peculiar, coincidental, or ironic, such as:

- The war started and ended at McLean’s Farmhouse.

- There is a photograph of John Wilkes Booth attending one of Lincoln’s speeches before the Civil War started.

- The only time Ulysses S. Grant was considered successful was as a general. He failed as a businessman and had a scandalous presidency.

- The abolitionists who broke laws to hide slaves were often religious leaders.

- Robert E. Lee was also asked to lead the military effort for the north, but he chose to fight for the south because he was loyal to Virginia.

- President Lincoln wanted to hear the song “Dixie” the day the war ended.

- When Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant met at West Point, Grant remembered meeting Lee, but Lee did not remember meeting Grant.

From this intriguing perspective, students authentically make connections to similar situations and leaders, in history or present day. Students become prepared to discuss current news and review what is happening in the world from various perspectives.

Students think at levels well beyond their ability to read and write. A desire to share their ideas as well as to learn more about the experiences and thinking of others is the best motivator to improve reading and writing skills. Mind mapping illuminates the thinking of children at every level in learning and allows them to share elevated ideas. When students can show what they know with images, icons, symbols, and words, every student can demonstrate their most complex ideas.

Scott describes an example of evidence of differentiated learning. Courtney and Addie love working together, both creative yet one talkative, the other more reflective. They playfully challenge each other. On their mind maps they began cutting rectangles of paper and gluing them to their mind map, so they opened like the windows or doors on an advent calendar. They called them “trap doors” and added them whimsically. Inside they added details about a person or topic and recorded jokes or secrets. Their civil war mind map had trap doors with 3-D surprises that popped out like a canon bomb or fireworks to celebrate a victory. These quirky surprises are why I like being around kids.

Mind maps can be created about literature, history, science, or social studies. Information is provided during reading instruction, watching documentaries, examining visual images, listening to pieces of music, watching plays, etc. For example, Mr. Flox shows a Ken Burns documentary on the Civil War while the students create a mind map and Mr. Flox stops and starts the video to have strategic conversations. During instruction, new conversations emerge between pairs and trios in the room and students converge as a group as the teacher directs.

As the teacher and students mind map, each person builds on their own strengths, makes decisions, and develops their judgment. The learning environment is transformed into a collective of individuals, each responsible for their own learning while enriching and supporting each other. Many needs of the gifted student and the resource student alike are addressed simultaneously through these student-centered strategies that invite open-ended answers for broad differentiation. Students decide where they want to go and how far. As a foundational piece of any classroom, mind mapping for learning interweaves effective teaching and learning strategies, making the job of the teacher and learner more rewarding.

Second grade teacher Glenda Butikofer shares how the culture of her classroom changed with mind mapping to encourage authentic discussions: “In my first mind mapping lesson, I was teaching about states of matter. I planned on talking about solids, liquids, and gasses, but as we got into our discussions, one of my boys that struggled to read and could not write legibly, raised his hand to let me know that there were other forms of matter, and told me all about plasma and related topics. My belief about what this boy could learn changed in that moment. I began to push learning to higher levels to engage all kids successfully. Using mind mapping, all kids can be successful, even the ones that struggle to write information down.”

Thought Mapping for Teacher Planning

Thought mapping is what teachers do to lead student thinking and connect concepts. Building a thought map clarifies the thinking that teachers want students to demonstrate in their mind maps. A thought map is the teacher’s lesson guide or outline for the lesson plan. This includes related core standards, selected learning outcomes, and key concepts. It provides the questions, prompts, and ideas of how to lead students through making a mind map. The thought map can also include “sample things to say” as described in the examples in the next section. Teachers should craft questions from each level of Bloom’s taxonomy and plan a related activity to do in the mind map to reinforce that skill: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, create. A mind mapping lesson should include the elements listed and defined below.

- Stories provide context, relevance, and personal connection. Personal stories instigate relationships, increase vulnerability, engage empathy, and allow us to compare/contrast our own experiences with those of others. In the classroom stories can be personal, historical, fictional, fantasy or even technical and non-fiction.

- Non-fiction information helps people understand the content of stories. Learners often need to check a dictionary definition or look up geographical/historical information to understand what actually happened in a story. The story piques curiosity for information about the world.

- Questions ignite curiosity, the most powerful motivator for learning. Open-ended questions evoke deep thinking. Directed questions guide students to selected learning outcomes.

- Personal reflection internalizes the information and the story, uncovering opinions, thoughts, and questions. Learners evaluate and internalize the information according to their own experiences.

- Conversations emerge from personal reflection as individuals seek answers to questions, listen to the thoughts and ideas of others and share their own. Words are metabolized into meaning through well-constructed conversations.

- Background knowledge and extensions of information include definitions, historical or geographic context, biographies, famous incidents, inventions, oddities, non-fiction information, theoretical frameworks, and any information that connects to the content being learned. Personal stories also provide background information. The more a student knows about the world, the easier it is to learn new information. Likewise, teachers who continually read about historical and current events are best prepared to make relevant real-world connections in the classroom. Suggested readings on topics related to this book are included in the text.

Steps for Teacher Planning

- Select the topic you want to mind map about.

- Create the essential questions to guide the learning. (An essential question restates the desired learning outcome in an interrogative format.)

- Create a list of core standards, required background knowledge, inspiring ideas and guiding questions about the content for the teacher to use as a cue sheet while teaching.

- Create a fact sheet for students to use listing what the students need to know as well as additional relevant information (15-30 items).

- Gather the needed information from various sources, videos, images, original source documents, leveled readers, etc.

- Apply the instructional strategies listed on page 62 to teach the needed information.

- Create a mind map specifically about the selected topic.

Mind Map Checklist for Literature

The primary purpose of mind mapping with literature is to illuminate thinking to improve the quality of conversations. Drawing gives students time to think, to analyze, and to assimilate information. In a classroom, students can draw and think simultaneously, but need to take turns speaking and listening. Preparing students with individual thinking and drawing time leads to more meaningful dialogue. Creating mind maps simultaneously, as a group, models for students a respectful balance between thinking, listening, and speaking time. Students get ideas from the mind maps and questions of others to add to their own work. As the conversations improve, so do the questions students ask. Creating quality questions encourages curiosity, which develops life-long learners. View student samples of mind maps.

|

Steps for Mind Mapping Literature |

Sample Things to Say and Do |

|

Identify and label the topic for the mind map. This could be the title of the book or the main idea. |

Put an icon, word, or other representation of the topic on the page. Put it in a space where you have a lot of room around it. Read the first and last sentence of this paragraph, then read the whole paragraph to determine the main idea. |

|

Identify the pieces of information that need to be included on the map. This could be characters, events, facts, setting, author, etc. Add a representation of each piece of information. |

Who is this story about? Put a picture, icon, or label on your paper about each of the main characters. Add dialogue bubbles to show what the characters would say or think. What is the setting? What were the main things that happened? Show evidence by including quotes, dialogue, or images. |

|

Further illustrate the pieces. |

Continue to illustrate and label each part of the story as you continue through the book. How does the setting change? How do the characters change? Discuss the cause and effect of why the character changed. What are the ramifications of the events in the story? |

| Sequence the pieces as you develop the map. | Add arrows or numbers to identify the order in which things happened. |

|

Develop extensions to the illustrations or words. |

Chart, graph, icons, Venn diagram -- What can you add that will show the idea more clearly and/or provide more detail? |

| Make connections/apply knowledge. | Make connections to background knowledge (see Chapter 7 for example frameworks for background knowledge), connect to other curricular standards, connect to other literature, identify similar facts, concepts, and themes, identify these connections through illustrations or words on the map as well as in conversation. |

| Summarize and extend thinking. | Add an analogy, simile and/or a metaphor to the map that connects to student knowledge. |

|

Engage in conversations and discuss the mind maps throughout the creation process. Give students feedback. |

In a whole group discussion, invite students to share with the class their metaphor for their mind map. Invite an individual student to explain their reasoning for including a certain image or portion of their map. |

|

Add additional ideas and representations until complete. |

Is there anything else you can add? What’s next? |

When preparing for mind mapping, help students organize their thinking by making a cause-and-effect chart. The chart can be labeled in two columns: cause and effect, or for a different perspective, list three columns: facts, adaptations and ramifications. List the facts of the story being discussed. List how the character or situation adapted to the events in the story. Summarize what the effect was. What were the ramifications of what happened in the story?

|

Fact |

Adaptation |

Ramification/effect |

Mind Map Checklist for Science

The primary purpose of mind mapping with science instruction is to assimilate facts and information into personal meaning and to move the information into long-term memory through illustration and dialogue. The information can be from short paragraphs, reference books, internet sources, or movies. Various sources coalesce in the map. A mind map can also serve as an outline for a research project, and the strategies can be used for the students to write a book with illustrations as an extension to go deeper into a selected topic.

|

Steps for Mind Mapping Science |

| Sample Things to Say and Do |

Identify and label the topic for the mind map. Is it an event, person, item, or phenomenon? |

| Put an icon, word, or other representation of the topic on the page. Put it in a space where you have a lot of room around it. |

Identify the pieces of information that need to be included on the map. Add a representation of each piece of information. |

| Function: What is the purpose or role of this item or occurrence? Identify the related parts. Events: What are the main things that are happening? Facts: Read the text, watch the video, observe the experiment and then paraphrase the factual information about the item or event. Write it on your map. What are the ramifications of this item/event existing or not existing? Is there a cause and effect relationship? Describe how this item/event could adapt to changing circumstances. |

|

Develop extensions to the illustrations or words. Give students feedback. |

| Go online, find and print-related diagrams, maps, charts, illustrations, etc. Cut and paste them on your mind map. Label and describe all the parts and draw connections to other items on the mind map. |

|

Summarize and extend thinking. |

| Write an analogy about a topic or an idea from your mind map that connects the data to student knowledge. |

Mind Map Checklist for Social Studies

The primary purpose of mind mapping in Social Studies instruction is to internalize the information so students can personalize and humanize the historical situation and experience. Another purpose is to illuminate and track the institutional and personal thinking of decision makers to improve the understanding of cause and effect. A variety of sources should be used: original documents, books, articles, images, videos, internet etc. Additional extensions are discussed in Chapter Six using contextual frameworks.

|

Steps for Mind Mapping Social Science |

| Sample Things to Say and Do |

Identify and label the topic for the mind map. Is it an event, animal, item, phenomenon? |

| Put an icon, word, or other representation of the topic on the page. Put it in a space where you have a lot of room around it. |

Identify the pieces of information that need to be included on the map. Add a representation of each piece of information. |

| Characters: Who does this situation impact or involve? Put a picture, icon, or label on your paper about each of the main characters and/or groups of people. Add dialogue bubbles depicting what the characters would say or think. Do a character study of each individual. Events: Identify the significant events both public and private. Facts: Identify the relevant geography, policies, cultural, or other facts that impact this story. What were the ramifications of decisions or situations that occurred? How does this situation or decision impact people, society and the world? |

|

Develop extensions to the illustrations or words. Give students feedback. |

| Go online, find and print related diagrams, maps, charts, illustrations, etc. Cut and paste them on your mind map. Label and describe all the parts and draw connections to other items on the mind map. |

|

Summarize and extend thinking. |

| Write an analogy about a topic or an idea from your mind map that connects to student knowledge. |

View student samples of mind maps.

Assessment

To assess students’ work on their mind maps, consider these criteria:

- Evidence of each type of thinking on Bloom’s Taxonomy

- The depth of the abstract connections they make

- The use of space e.g. filling the page, both positive and negative space

- Formatting of their illustrations with labels and/or captions

- Adding illustrations to labels, titles, and terms

- Details shown in either illustrations or explanations

- Connections made from other discussions in various subjects, novels, and guided reading facts and so forth.

- Connections to personal experiences

- Other divergent thinking ideas represented

- Effort--did they exceed their expectations or yours?

Reflection

- What inspires you to create?

- When do you feel creative in your classroom?

- Which ideas from mind mapping describe what is already happening in your classroom?

- Which ideas would you like to add to your classroom?

- Make a mind map about you. What describes and defines you?

Want to Know More?

Mind Mapping by Tony Buzan

Creating Meaning Through Literature and the Arts by Claudia Cornett

Studio Thinking: the real benefits of arts education by Lois Hetland, Ellen Winner, Shirley Veenema, Kimberly M. Sheridan