Copyright

As you begin creating your course, you will often use existing resources that others have created, such as books, journal articles, images, videos, etc. You will also likely create your own resources that may be useful as stand-alone content, such as an illustrative image of a difficult concept. In all of these cases, legal frameworks exist that determine what you can and cannot legally use, when permissions are needed, and what rights you have over your own creations. In this chapter, we will address the basics of copyright law and guide you in conducting a copyright audit for formative evaluation purposes.

Learning Outcome

I can use copyrighted material while adhering to applicable laws.

Sub-section outcomes:

I can reasonably determine whether fair use applies to specific copyright cases. (Section 8.1)

I can use public domain resources to improve my course design. (Section 8.2)

I can interpret the meaning of open licenses, use open content, and choose appropriate licenses for my own works. (Section 8.3)

8.0 Introduction

Copyright is typically established in federal law and varies from country to country. In the U.S., copyright was written into the original constitution in 1787, where it was stated that copyright is established "to promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries" (Article 1.8.8). It does this by giving creators control over their creative works for a specified period of time so that they can profit from them, thereby encouraging them to create more.

Video 8-1

Copyright basics for teachers

8.0.1 Copyrighted Works

Historically, copyright applied to any tangible creative work, such as a book, movie, video, song, lyric, poem, picture, lesson plan, etc. With the advent of the internet and electronic tools, not all creative works are produced in a "tangible" medium, so this protection has been expanded to include electronic works as well. This includes code and digital resources, like streaming videos, audio files, image files, documents, etc. Advancing technologies, ranging from the player piano to the internet, have always had unintended consequences for copyright law, and copyright law has always been slow to keep up with advancing technologies. Copyright law has changed over time, but as new technologies empower us to share and use copyrighted materials in new ways and at greater scale, copyright law gradually changes in response.

8.0.2 Uncopyrightable Work

Intangibles, such as ideas, concepts, and mathematical equations and works that lack originality cannot be copyrighted. This means that you do not need permission to copy the Pythagorean theorem, Einstein's mass-energy equivalence equation, or Newton's laws. It also means that you can freely talk about Jupiter, the Renaissance, or transformative uses of technology without permission or citations. If you wanted to copy a book or a movie clip that references these ideas, concepts, or equations, then copyright would apply to the work but not to the idea itself. So, when YouTube creators want to make a video about the physics concept of relativity as it is used in the movie Interstellar, copyright does not apply to the concept of relativity (so they are free to talk about it), but copyright does apply to the movie Interstellar (so how they use movie clips will be subject to copyright).

Figure 8-1

YouTube results for "Interstellar relativity" and a monkey taking a selfie

Other important cases of uncopyrightable work include works created by non-humans, such as selfies taken by a monkey, paintings made by a robot, and content created by artificial intelligence. This becomes a bit complex when we consider that a painting robot was created by a human or that an artificial intelligence may have been trained on copyrighted works, and this aspect of copyright law will likely continue to evolve, but current application of copyright law in the U.S. limits copyright claims to immediate human creators of a work. Any works created by non-humans are in the public domain.

8.0.3 Gaining Copyright

In the U.S., copyright is automatic. It applies to a work as soon as it is created, and the author does not need to do anything to make this happen. There is no required process for applying copyright to a work; the work is copyrighted, period. This means that anything created by anyone is copyrighted automatically, whether the creator wants it to be copyrighted or not. So, as soon as Tolkien penned ink to paper on The Hobbit or James Cameron and his cinematographers captured video for the movie Alien, those works were copyrighted instantly.

However, proving that you hold the copyright on your creative work is another matter. For instance, say that you write a novel and lend the manuscript to your neighbor to proofread. What is to prevent your neighbor from claiming that the novel is her creative work and, therefore, claiming to hold its copyright? To help in preventing and addressing copyright problems, the U.S. government allows copyright holders to register copyright with the U.S. copyright office. Thus, while an author does not need to do anything to copyright a work, they do need to go through a process if they would like to register the copyright of that work to safeguard against infringement or to initiate a lawsuit.

8.0.4 The Copyright Symbol ©

The copyright symbol may be placed on a work to remind and inform users of its copyright status: ©. However, the copyright symbol is only a reminder. The absence of the symbol does not mean that the work is not copyrighted, and the presence of the symbol is not proof that the work is copyrighted. The symbol is a notification and a warning, but it may not be accurate.

8.0.5 Ownership

By default, the author of a work holds the copyright on that work. The main exception to this rule would be if the author was being paid by someone else to create the work and the author had signed a contract stating that the work was created specifically as part of their job. In copyright law, this is called a "work for hire." So, if you hire a graphic designer to create a cover for your book, because they are specifically hired to create this thing for you, you will own the copyright on it when they are done. Contracts might also stipulate that ownership depends upon when and where the work was created (during standard work hours vs. after work hours or in the office vs. at home). Designers and course developers are typically viewed as creating works for hire, so course materials they create are owned by their institutions. However the case of educators, especially professors, is a bit messier. Some educator contracts state that creative works by an educator are owned by the educator, while others state that they are owned by the school, district, or university. If you would like to know who holds the copyright of works you create as part of your job, you should check your teaching contract or contact your employer.

8.0.6 Usage

Copyright generally means that others cannot use copyrighted material without the permission of the author and that permissions are restrictive. For instance, downloading a bootleg version of a movie is a violation of copyright, because you did not purchase the copy from the copyright holder. Further, even if you do purchase the movie from the copyright holder, you can only use the movie in the ways that the copyright holder allows (e.g., for private home use, not for public screenings). Thus, by purchasing a copy of a work, you do not "own" that work in the sense that you are not free to do whatever you like with it. You must still abide by any copyright restrictions placed on the work, which might determine how and where you use the work, your ability to make copies of the work, and your ability to modify the work.

8.0.7 Linking

You can generally provide a web link to copyrighted material from your own materials without permission from the copyright holder. This is different from copying/pasting the copyrighted material into your own work because it allows the copyright holder to maintain control of their content and to generate revenue through web traffic. The primary exception to this rule would be if you provided a link to materials that should not be publicly accessible and, therefore, allowed your learners to bypass restrictions placed on the content by the copyright holder.

8.0.8 Losing Copyright

Copyright comes with a time limit. The purpose of this is that the U.S. government recognizes that copyright can only benefit the copyright holder for so long and that at some point copyright should expire. Currently, the U.S. copyright law states that copyright ends 70 years after the death of the author. Upon expiration, copyrighted materials move into the public domain. Copyrighted materials may also lose their copyright status under other conditions. For instance, a copyright holder may relinquish the copyright status on their work, thereby allowing it to pass into the public domain.

8.0.9 Permission

If you would like to use copyrighted material, you generally need permission from the copyright holder, but once a copyright holder gives you written permission to make copies of content or to include something in your course, then you are free to do so. The original creator of the work is typically the copyright holder, but in some cases they might have signed the copyright over to someone else (e.g., a published book is generally copyrighted by the publisher, not the author). So, if you want permission to use something, you will first need to identify the copyright holder and then seek permission from them to use the work in your desired manner.

8.0.10 Risk

Many professionals are not aware of copyright law simply because their jobs do not place them at risk of being sued for violating them. K-12 classroom teachers, for instance, typically work in a closed classroom that is not visible to the outside world. So, if they violated copyright in their classrooms, no one would really know, and there's little chance of being targeted by copyright owners. This perceived safety, however, breeds misunderstanding as many educators think their copyright violations are lawful simply because they are educators when in actuality their illegal behaviors just simply have not been brought to light. The result is that many professionals persist in dubious or unlawful behaviors simply because there is little risk that they will be discovered.

When developing online courses, however, this risk is greatly increased, because content can be shared and recorded. What might have been done behind closed doors previously is now visible to the world, and this increases the risk that copyright violations will be recognized and acted against. For this reason, online course developers should both be aware of copyright law and abide by copyright requirements. Failing to do so may open you or your employer up to lawsuits and other punitive legal action and also serves as a poor model of digital citizenship to learners, leading them to continue a cycle of unknowingly illegal activity.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I legally show my students videos from my Netflix account or other subscription streaming services?

No. Your license agreement does not allow you to do this.

When is a work copyrighted?

As soon as it is created or published.

Does a work need to be published to be copyrighted?

No, though it must be in some physical form (e.g., manuscript, recording).

Does an author need to register their work in order for it to be copyrighted?

No. Authors may register their work with the US copyright office to protect against infringement, but even unregistered works are copyrighted.

If something is labeled with a copyright symbol (i.e., ©), does that mean it is copyrighted?

Maybe. The symbol serves as a reminder, but the copyright might have expired.

If something is not labeled with a copyright symbol (i.e., ©), then is it copyrighted?

Maybe. Maybe not. The label has nothing to do with whether or not a work is copyrighted. The copyright label only serves to remind and to inform. If you see no label, you should assume that the work is copyrighted and look into the matter further.

Can I link to copyrighted materials?

In most cases, yes. As the name implies, copyright only takes effect when you make a copy something. Just be sure that you are linking to the resource as it is provided by the publisher (not uploaded to someone's personal server, etc.) and that your link does not bypass a copyright holder's login system. If it does, then you can potentially be in violation of other laws, like cybersecurity and anti-hacking laws.

Can I embed copyrighted materials into my presentation or website (e.g., YouTube videos)?

Generally, if a site like YouTube gives you an embed script, then you are able to use it (provided that you do not change the script, remove attribution, etc.). Fair use doesn't apply in cases like this, because the copyright holder has given you permission to do it. So, as long as you don't deviate from what they've allowed, then you're fine.

Learning Check

If you find a work online that does not have the copyright symbol on it, what should you assume?

- That it is in the public domain because all copyrighted works have a copyright symbol.

- That it may be copyrighted but it probably isn't because if it was copyrighted then the author would have included the symbol.

- That it is probably copyrighted, but if it is an old work then the copyright might have expired.

- That it is copyrighted because everything is copyrighted unless explicitly stated otherwise.

When does copyright begin on a creative work (e.g., image, photograph, book, movie)?

- The date when the work has been approved for copyright by the Copyright Administration or BMA.

- The date when the copyright symbol is placed on the work.

- The date when the work is created.

- The date when the author is born.

8.1 Fair Use

Learning Outcome: I can reasonably determine whether fair use applies to specific copyright cases.

Fair use is an exception or limitation to copyright law that allows you to use some copyrighted materials in particular circumstances without the copyright holder's permission. However, fair use is widely misunderstood, with many educators believing that they can do whatever they want under the auspices of fair use. Fair use, however, can actually be very complicated, applies equally to everyone, and operates under the four guiding principles:

"Fair Use" Guiding Principles

Nature of Use

Type of Work

Amount Used

Commercial Impact

Myths of Fair Use

Some common myths of fair use include the following:

Educators and non-profits are exempt from copyright rules because of fair use.

Fair use does not apply to educational uses of copyrighted work.

Saying "no copyright infringement intended" makes a use fair.

Using fewer than X pages of a book, X% of a song, or X minutes of a video is fair.

To understand what uses of copyrighted material are actually fair, we will now briefly explore the four guiding principles.

8.1.1 Principle 1. Nature of Use

The first principle covers what you are doing with the content and whether your use aligns with the author's intended use. Fair use only applies to uses of works that are transformative in nature. This means that your intended use must be different from the author's intended use. Consider a novel. You can quote lines from a novel in a paper you write without permission from the novel's author, because you are writing the paper to analyze literary elements of the novel, not to tell a story. If, however, you took those same lines and placed them in your own novel, then that would not be an example of fair use, because your intended use would be the same as the original author's intended use. In education, this means that using someone else's educational content (e.g., an image from their textbook) would not generally be fair use, because your intent is the same as theirs (i.e., educational and, therefore, non-transformative).

8.1.2 Principle 2. Type of Work

The second principle gives greater flexibility in using informational or factual works than to artistic or creative works. Thus, copying a few pages from an encyclopedia is viewed as more conducive to fair use than doing the same with a detective novel, because the information's benefit to society is readily apparent.

8.1.3 Principle 3. Amount Used

The third principle ensures that you only use as much of the copyrighted material as is necessary to achieve your goal. Thus, quoting a line from a novel would be considered fair use, but copying multiple chapters of the novel for this purpose would not. This is both a quantitative and qualitative consideration, in that you should not use more than is needed but fair use also should avoid using the "heart" of a work.

However, there is no magic number here. A judge will not look at your use and ask "did they use fewer than 10 pages" but will rather ask "is the amount used reasonable."

8.1.4 Principle 4. Commercial Impact

And the fourth principle considers whether copyrighted material negatively impacts the author's ability to profit from it. If you copy an article to share with your class, this would prevent the copyright holder from selling access to the article, which would be a violation. However, if you were to copy only a paragraph of an article for this purpose, it is less feasible that the copyright holder would potentially lose money on this use. So, this use would be more defensible as fair use.

8.1.5 Applying the Principles

If it weren't for fair use, you wouldn't even be able to write a paper that quoted a famous author without permission, which would be a serious matter for scholarly progress. Consider this poem from The Fellowship of the Ring:

All that is gold does not glitter, not all those who wander are lost; the old that is strong does not wither, deep roots are not reached by the frost. J. R. R. Tolkien

Without fair use, the inclusion of this poem in a paper on literary analysis or on this website would be a copyright violation, because I did not seek the author's prior consent to make a copy of this text from his book or to distribute it online. However, my use in this case is a transformative use and is only large enough to make the educational point, so it is allowable. Would being able to read this quote on this website prevent someone from reading his book (thereby depriving the copyright owner of profits)? Certainly not. On the contrary, however, if I were to provide several chapters of Tolkien's book online without prior permission from the copyright holder, then this would not constitute fair use.

Similarly, copying another teacher's lesson plan, changing a few words, and posting it online would be a blatant copyright violation. Fair use becomes problematic in education if you are trying to use educational works in your own creations (e.g., materials created specifically for education, such as lesson plans or textbook chapters) and/or you are using too much (such that it might prevent the owner of the copyright from profiting from the work).

To determine if a desired use of copyright-restricted material would fall under fair use, ask yourself four questions:

Use: Is the use transformative? (Yes = Fair Use)

Type: Is the work informational/factual in nature? (Yes = Fair Use)

Amount: Is the use minimal? (Yes = Fair Use)

Impact: Does the use negatively impact the copyright holder's ability to profit from the work? (No = Fair Use)

Fair use is a judgment call, but the call is made based on the answers to these four questions. Thus, if your answer to all four questions aligns with fair use, then your use would likely be judged as fair. If the answer to one question does not align with fair use, then your use might still be fair, but it increases the potential for it to be judged otherwise. And so forth. In many court cases, uses that met three criteria have been deemed as fair, and in others, uses that only met one or two criteria have been deemed as fair, but there is never any guarantee. In short, only a judge can determine if use is fair, but a judge would use these four guidelines in making the determination.

Positive Examples

These are examples that would probably qualify as fair use (i.e. they probably do not violate copyright):

Quoting a few sentences from a book in a paper on literary criticism;

Adding text to a movie screenshot to critique/parody the movie;

Including a paragraph of text from a book in a quiz as background for asking questions;

Showing a short clip from a popular movie to analyze how it was made.

Negative Examples

These are examples that would probably NOT qualify as fair use (i.e., they probably violate copyright):

Copying pages from a workbook for students to complete;

Copying or remixing a lesson plan;

Creating a calendar of pictures that were photographed by someone else;

Including a popular song as background music on a YouTube video your students create;

Holding a public screening of a movie that you have purchased for personal use.

To help safeguard your fair use claims, many institutions require their designers to complete a Fair Use Checklist for any creative work they are using in their coursework. These checklists may vary by institution, but their intent is to provide a positive defense against copyright infringement claims by showing that you have a case for showing that your use is fair.

Blueprint Challenge

Complete the Fair Use Checklist for a textual or media item (e.g., image) that you will use in your course.

8.1.6 Institutional Rules

To help safeguard themselves and their employees, many educational institutions will also adopt rules for interpreting fair use. For instance, some institutions will allow copyrighted materials to be used up to a certain percent of the work (e.g., a section of a book can be copied as long as it constitutes 10% or less of the entire book). These rules are not perfect reflections of the law but are rather interpretations intended to protect. Thus, when considering institutional rules, you should recognize that they are intended to prevent you from breaking a rather fuzzy law but that they also may not entirely reflect what the law actually states. In any case, you are safest abiding by your institutional rules for fair use, because this helps to ensure that your institution will be on your side if there is any question about your copyright-restricted material use.

Figure 8-2

John Wayne thinks fair use is confusing

8.1.7 The Bottom Line

Fair use is complicated and confusing, only provides educators with limited opportunities for use, and is typically more of a headache than it is often worth when talking about any substantive use of copyrighted materials. At times, you will need to use copyrighted works in your course, but thankfully, there are other alternatives, such as public domain works and openly licensed works, which we will now explore.

Additional Resources

The U.S. Government archives court cases related to fair use, which may be instructive if you have specific questions about what courts are classifying as fair use and not.

8.2 Public Domain

Learning Outcome: I can use public domain resources to improve my course design.

According to copyright law, there are some creative works to which copyright does not apply. These are public domain works or works in the public domain. The largest group of these works are simply those works that are old enough that copyright no longer applies, but this will vary by country and the year in which the work was created.

Simply finding a work in a public place does not mean it is in the public domain. Rather, your default assumption should be that any work you find is copyrighted unless it is clear that it is in the public domain. However, if you do find a work that is in the public domain, then it is free game for you to use as a designer. You can do whatever you want with it (without permission) and do not even need to cite the original author to meet copyright requirements.

Myths of the Public Domain

Some common myths of the public domain include the following:

If a work is visible publicly, then it is in the public domain.

If something is free, then it is in the public domain.

Royalty-free is the same as public domain.

Fair use is the same as public domain.

8.2.1 Categories

In general, there are three groups of works that are in the public domain:

Old works for which the copyright has expired;

Exempt works that may not be copyrighted or that were created under certain conditions;

Any works that have been released to the public domain by their authors.

We'll now explore each in more detail.

Old Works

Under the current US copyright law, any copyrighted work will automatically pass into the public domain 70 years after the death of the creator. In general terms, this means that almost all classics or materials older than 120 years or so are in the public domain. To determine if a specific work is in the public domain, you should find out when the author died and add 70 years in order to determine the date at which copyright expires. This time frame has gradually been lengthened in US history, so some works may still be in the public domain that were created less than 70 years ago.

Figure 8-3

The movie "McLintock!" and many other works are in the public domain

The John Wayne and Maureen O'Hara movie McLintock! passed into the public domain in 1994.

Various other works are in the public domain

Exempt Works

In addition to uncopyrightable work described above, some works may also be exempt from copyright if they are created under certain conditions of employment. The most common example of this is when US federal employees create works as part of their jobs (e.g., active duty service personnel in the armed forces). Works that these individuals create (e.g., photos taken) may be placed in the public domain by virtue of their employment as is the case with photos taken by U.S. Fish and Wildlife employees.

Released Works

In addition, the creator of a work may willingly choose to release that work into the public domain by simply labelling the work as public domain (e.g., "this work is in the public domain"). By doing so, the author gives anyone—including individuals, corporations, and governments—the right to use their work for any purpose, without limitation or attribution.

8.2.2 Use

Since they are not subject to copyright protection, public domain works may be used for anything and may even be included in derivative works and may be sold. For this reason, you could take Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice and remix it to Pride and Prejudice and Vampires without seeking permission or violating copyright. You could also take the book Moby Dick, replace every reference to a whale with a dragon, and make it a fantasy novel. You could then make movies or commercial books with these derivatives.

The entire Disney empire was built on this model of taking preexisting content and remixing it without permission or attribution, as with Snow White, Cinderella, Beauty and the Beast, Sleeping Beauty, etc. In these cases, the remix is subject to copyright protection, but the original is not. So, you could make your own version of Cinderella as long as you worked from the original storybook and not from the Disney remake.

Furthermore, there are no restrictions on how these works may be used, so citations are not generally needed. However, if you are using public domain content in your own work, it would be helpful for others to know what parts are public domain so that they know how they might also reuse and remix your content.

Public Domain Repositories

Some examples of online repositories that collect public domain works include the following:

Learning Check

What is the best definition of "public domain" as it relates to copyright?

- Public domain refers to content that is awaiting approval by the copyright administration.

- Public domain refers to any type of content that is not copyrighted (due to age or any other reason).

- Public domain refers to any type of content that is publicly visible (e.g., a website).

- Public domain refers to any type of content that has been shared by a reputable source (e.g., news site).

Which of the following are examples of (legitimate) Fair Use?

- Using a popular song as background music to a video you are posting to YouTube.

- Copying several chapters of a novel to distribute to your students.

- Copying a lesson plan from a textbook and sharing it with other teachers in your district.

- Quoting a few sentences from a novel in a paper so that you can analyze the meaning of the passage.

- Making additional copies of a student workbook.

Which factors determine whether the use of a work would be classified as Fair Use?

- Short: It only uses a very small portion of the work.

- Transformative: It is used for a different purpose than that which was intended by the author.

- Intention: You are not intending to violate copyright.

- Non-Commercial: You are not profiting monetarily from the work.

Which of the following are ways in which a work could enter the public domain.

- The work was created by a teacher.

- The author releases the work to the public domain.

- The work is very old.

- There is no copyright symbol on it.

If you use a work in the public domain, you are NOT legally required to cite it.

- True

- False

Which of the following are examples of works in the public domain?

- J.K. Rowling's "Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban" (first published in 1997)

- Jane Austen's "Pride and Prejudice" (first published in 1813)

- Shakespeare's sonnets (written between 1592 and 1598)

- Wikipedia articles

In the current U.S. law, how long does copyright last?

- 28 years after the work was created

- Life of the author, plus 70 years

- Life of the author, plus 50 years

- 60 years after the work was created

Clarification: Royalty-Free Licenses

Royalty-free does not mean public domain. If an image or other resource is released under a royalty-free license this means that copyright restrictions still apply but that you may be able to make a limited number of copies as long as you do not use them in a website banner, do not use them in a logo, etc. "Royalty-free" can have a variety of meanings, and if you wish to use a royalty-free work, then you will need to carefully read and understand the the fine print in the individual case you are considering. "Royalty-free" does not mean free but merely means that there are situations wherein you might not owe the creator money for using their work.

8.3 Open Educational Resources

Learning Outcome: I can interpret the meaning of open licenses, use open content, and choose appropriate licenses for my own works.

Though public domain works are very useful for course creation, there main drawbacks are that most public domain works are old and that there may not be many useful resources available for every subject area. As another option, open educational resources have gained prominence as a way to share and use content freely without authors fully giving away their copyright protections to the public domain. Open educational resources are materials that are released under an open copyright license, which allows course creators and others to freely use them without permission or unnecessary copyright restrictions.

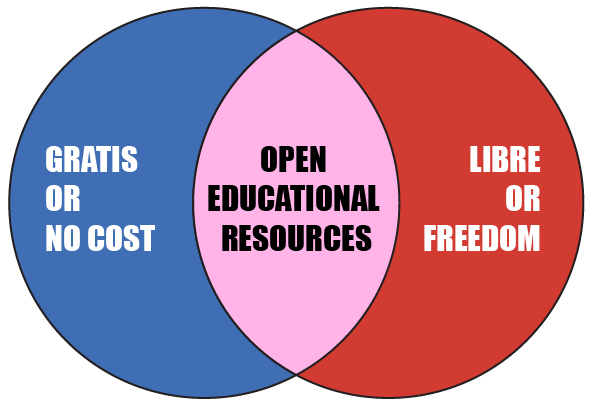

The terms "open" and "free" colloquially have many meanings. "Free" generally has two that may be best understood by referring to their latin equivalents: gratis and libre. In the context of openly licensed materials or Open Educational Resources (OER), gratis means that content and resources are provided at no cost, while libre means that you have the freedom to do what you want with these resources.

As an example of this distinction, you may find a website with "free" videos or another teacher may give you a set of old textbooks for "free" (i.e.gratis), but you are not then able to do whatever you want with those videos and textbooks (i.e., not libre). Similarly, Facebook is a gratis service, because you do not pay a fee to use it, but it is not a libre service, because you have only limited access to download, delete, or control your data. This is an important distinction, because many gratis resources are not libre, and when we talk about openness, we mean both gratis and libre.

Figure 8-4

Open educational resources have the characteristics of having no cost and allowing you to exercise freedom

8.3.1 The Five "R's" of Openness

Openness may mean different things to different people, and the freedom aspect of openness is often what people have the most difficulty understanding. To help with this, Wiley (n.d.) has articulated the five R's of openness as follows:

Retain

Reuse

Redistribute

Revise

Remix

Using this framework, an open educational resource is one that (1) you can retain access to forever, (2) you can reuse at multiple times or in multiple ways, (3) you can redistribute or share with others, (4) you can revise, adjust, and update forever, and (5) you can remix with other resources. None of these freedoms are allowed under a typical blanket copyright restriction, but with open educational resources, designers, educators, and learners are free to do many things that they otherwise would not be able to.

8.3.2 Open Licenses

Rather than circumventing or replacing copyright law, open educational resources operate by adopting specific open licenses that signal to others how they can use a created work without violating copyright, thereby preventing the need to contact the original creator to seek permission. By releasing a work under an open license, creators ensure that their work can be freely used and that others know what they need to do to abide by the creator's wishes. As such, open licenses find a nice balance between the restrictions of copyright and the unfettered freedoms of public domain, making them a good option for anyone desiring to share their work with others. In most educational settings, the most popular licenses used are Creative Commons licenses, while in other settings like software development GNU, MIT, and other licenses are prevalent.

Table 8-1

Common Open Licenses

Name | Image | Links |

|---|---|---|

Creative Commons |  | |

GNU General Public License (GNU-GPL) |  | |

MIT License |  |

8.3.3 Creative Commons

Creative Commons is a non-profit organization that has created a series of licenses that can be used by content creators to release their work openly. Many works found on the internet are licensed under one of these types of licenses, and in general, you do not need permission to use them in your work as long as you properly attribute (cite) them and abide by any additional requirements set forth in the license.

There are currently eight (8) different Creative Commons licenses. Two are merely restatements of Public Domain, while the rest provide the author of a work the ability to retain varying levels of control of how the work may be used. The most general Creative Commons license is the CC BY or Creative Commons Attribution license, which basically means that others are free to retain, reuse, redistribute, revise, and remix the creation as long as they properly cite the author. More information about each license is provided in the following table.

Table 8-2

Creative Commons License Brief Explanation Table

License Type | Image | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

Public Domain - By Age |  | These works are not subject to copyright or their copyright has expired. |

Public Domain - Released |  | These works are released to the public domain by their authors before the copyright has expired. |

Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) |  | Others may reuse, redistribute, revise, and remix the creation as long as they cite you. |

Creative Commons Attribution - Share Alike (CC BY-SA) |  | Others may reuse, redistribute, revise, and remix the creation as long as they cite you and share their creation under an identical license. |

Creative Commons Attribution - No Derivatives (CC BY-ND) |  | Others may reuse and redistribute the creation as long as they cite you. They may not remix it or revise it. |

Creative Commons Attribution - Non-Commercial (CC BY-NC) |  | Others may reuse, redistribute, revise, and remix the creation as long as they cite you, but they may not use your creation for commercial purposes. |

Creative Commons Attribution - Non-Commercial - Share Alike (CC BY-NC-SA) |  | Others may reuse, redistribute, revise, and remix the creation as long as they cite you and share their creation under an identical license. They may not use your creation for commercial purposes. |

Creative Commons Attribution - Non-Commercial - No Derivatives (CC BY-NC-ND) |  | Others may reuse and redistribute the creation as long as they cite you. They may not remix it, revise it, or use it for commercial purposes. |

8.3.4 Open Content Providers

Open educational resources (OER) are made available from many different sources. The following list, though not exhaustive, includes some of the more prominent providers. Explore these resources to find material that will be useful for you in your classroom, taking note of what licenses resources are released under. Watch this video to learn how to use a search engine to find openly licensed content.

Open Textbooks & Curricula

Search Engines

Google Advanced Search (set the "usage rights" field)

Google Advanced Image Search (set the "usage rights" field)

Yahoo Image Search (set the "Filter > Usage Rights" value in the results)

Text Content Providers

Wikipedia: open encyclopedia

Simple English Wikipedia: simplified encyclopedia

Project Gutenberg: public domain texts

Wiki Source: source materials

Wiki Quote: quotations

Media Content Providers

Wikimedia Commons: open media

LibriVox: public domain audio books

Internet Archive: public domain works

U.S. Army: public domain images

Library of Congress: public domain works

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Digital Library: public domain works (mostly)

Open Courses

Learning Check

Which of the following are true of openly licensed (e.g., Creative Commons) works?

- You do not need the permission of the author to use them.

- They do not need to be cited.

- They are free as in cost ($0).

- You can do whatever you want with them without consideration for the author's wishes.

If you see a work with a symbol that says "CC BY" on it, what does this mean?

- It is released under a Creative Commons (Attribution) license, and you can use it for anything as long as you properly cite it.

- It is close captioned. This has nothing to do with copyright.

- It is copyrighted by someone and cannot be used without permission.

If you see a work with a symbol that says "CC BY-ND" on it, this means that the CC BY license applies, plus what else?

- Non-Derivative

- Non-Distributable

- Needs Dates

- Needs Directions

If you see a work with a symbol that says "CC BY-SA" on it, this means that the CC BY license applies, plus what else?

- Show Attribution

- Signal Author

- Share Alike

- Simulated Area

If you see a work with a symbol that says "CC BY-NC" on it, this means that the CC BY license applies, plus what else?

- Needs Collaboration

- Non-Creative

- Non-Commercial

- Needs Citation

Which of the following works are the most free (as in freedom)?

- Copyrighted

- GNU GPL

- Public Domain

- Creative Commons

8.3.5 Attribution

When utilizing someone else's work in your own, you should be sure to attribute the work. In education, we generally use formatting guidelines from the American Psychological Association (APA), and you should cite works according to these guidelines if required for a research paper or publication. However, in most situations, a simpler citation that includes the work's title, author, license, and url will be appropriate. All work licensed under an open license will generally require you to properly attribute (cite) the resource in order to use it in your own work. Failure to properly cite one of these works if it is used in your own work is a violation of copyright. At minimum, you should attribute such works with the following information:

Attribution Items

Title

What is the title of the work (e.g., name of article, picture, or song)?

Author

Who created the work?

Source

Where did you find the work (e.g., url)?

License

What license is the work shared under (e.g., CC BY)?

As possible, you should also cite these works in such a way that it is clear to which portions of content the attribution refers and so that the attribution is prominent. For instance, if you include a Creative Commons image in a book you are writing, the attribution should be included as a caption under the image. When such attribution is not possible, including attributions in a works cited page is acceptable if it is clear to which content each reference belongs (e.g., providing page numbers).

Common Questions

If there is no author mentioned, how do I cite the resource?

Use the author of the website. If the website does not have a mentioned author, use the name of the website (e.g., "CK-12").

What if there is no copyleft license or notice of public domain mentioned?

Remember, just because no copyright symbol is present does not mean that the work is open (e.g., not every page of a Harry Potter book has a copyright symbol on it, but it is still copyrighted). Since everything is automatically copyrighted, you should generally assume that all work is copyrighted and should not treat it as an open resource without further investigation.

May I use a copyrighted work if I properly cite the author?

This depends on what you are using it for (see the discussion of fair use), but generally, you must have written permission to use it in any significant way.

If something is marked as released under Creative Commons, but there is no specific license identified, which should I use?

You should probably either use the most restrictive license (CC BY-NC-ND) or the most common license (CC BY). Use your best judgment.

Can I modify or revise an openly licensed work?

This depends on the license. In most cases, yes, but you may need to release your new work under the same license. The primary times when you cannot do this would be when the license prohibits derivative works (e.g., any CC BY-ND and CC BY-NC-ND).

Can I use Royalty Free work?

This is tricky. Royalty Free does not generally mean free as in libre (i.e., free to use for whatever). Rather, it typically means that you can use a work in a very specific way (e.g., print an image up to ten times) that will vary based upon the provider. So, royalty free is essentially just another way of saying copyrighted, but the material might be able to be used in some very limited manner without paying a fee.

If something is copyrighted, does that mean I cannot ever use it?

You can use it if you have the copyright holder's permission. You can always contact the owner and ask her/him if you can use it. Open resources are handy, simply because they make it easier for you to use materials without asking permission every time you want to use something.

8.3.6 Sharing Your Work

As the author of a creative work, you can release your it under an open license or into the public domain. All you need to do is place the Creative Commons license on your work or state that the work is in the public domain, and this allows others to know how they can use it. For example, by simply placing "CC BY 3.0" below a picture, you give anyone the right to use it for any purpose as long as they attribute you as the author.

Public Domain vs. Creative Commons

As the author of a creative work, you should consider the benefits of different ways of sharing your content. If you don't care how it's used but just want others to be free to use it, release it into the public domain. If you want to receive credit (be cited) when others use it, use CC BY 3.0. For a more detailed walkthrough of how you should release your content, follow the steps provided in the table below.

Table 8-3

Workflow for Choosing a License

Step | Question | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | Do you want to allow others to use your work without asking permission? | Go to Step 2 | Copyright |

2 | Do you want to receive credit for your work by requiring others to cite you? | Go to Step 3 | Public Domain |

3 | Do you want to make sure that anyone who uses your work also shares their work in the same way? | Go to Step 4 | Go to Step 5 |

4 | Do you want to prevent others from profiting from your work? | CC BY-NC-SA | CC BY-SA |

5 | Do you want to prevent people from changing your work? | Go to Step 6 | CC BY |

6 | Do you want to prevent others from profiting from your work? | CC BY-NC-ND | CC BY-ND |

Example Statements

Releasing your work under an open license is easy. Just place a statement somewhere on your work that states what license you are releasing it under. The Creative Commons site provides a wizard to create a statement and image for you, or here are a few more examples:

This work is released under a CC BY 3.0 open license by [Your Name Here].

This work is released into the public domain.

Conclusion

This chapter has provided an overview of copyright, public domain, fair use, and open licenses. With this you should feel sufficiently knowledgeable to use copyright-restricted, open, and public domain resources in a legal manner.

Blueprint Challenge

Complete a Copyright Audit for five (5) textual or media items (e.g., image) that you will use in your course.

References

Wiley, D. (n.d.). Defining the “Open” in Open Content and Open Educational Resources. improving learning. https://opencontent.org/definition